Biography

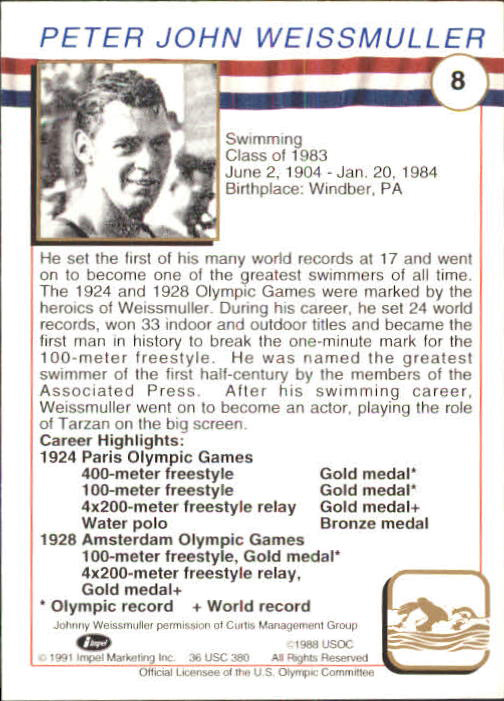

On June 2, 1904 Janos (Johann) Peter Weissmuller was born to German parents in Freidorf, Romania, at the time part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. He was baptized as a Catholic three days later on June 5.

On January 26, 1905 a seven month old Janos arrived at Ellis Island on the S.S. Rotterdam, after a trip of twelve days from Holland. Peter Weissmuller, a miner, and his wife Elizabeth nee Kersch were 27 and 24 years old respectively, and had only ten dollars along with their first-born child. They traveled by train to Windber, Pennsylvania to stay with family members. His brother Peter was born there in September.

In 1908 the family moved west to Chicago, where they reunited with Elizabeth’s parents, who lived on a farm nearby in a humble community of Freidorf colony immigrants.

The family rented a single floor in a shared house for the entirety of his youth, 4 blocks from Lincoln Park; his frequent trips to the nearby zoo helped to instill his early love of animals. As part of a city program with horses, he even learned how to ride bareback – a skill which would later serve him well in the role of Tarzan.

Johnny attended St. Michael’s school and served as an altar boy there, up until age twelve when he switched to public school. Once his father abandoned the family, Johnny had to leave school after the eighth grade and went to work at an early age to help support his little brother and mom, who worked as a cook. He delivered packages for a church supply company and hawked produce from a cart…later in life he said:

“You know, your guts get so mad when you try to fight poverty… I told myself, “I’m going to get out of this neighborhood, if only because he’s got a quarter and I haven’t.”

His mother Elizabeth worked hard to give the boys the best life possible within their modest means, and he remained very close to her throughout their lives.

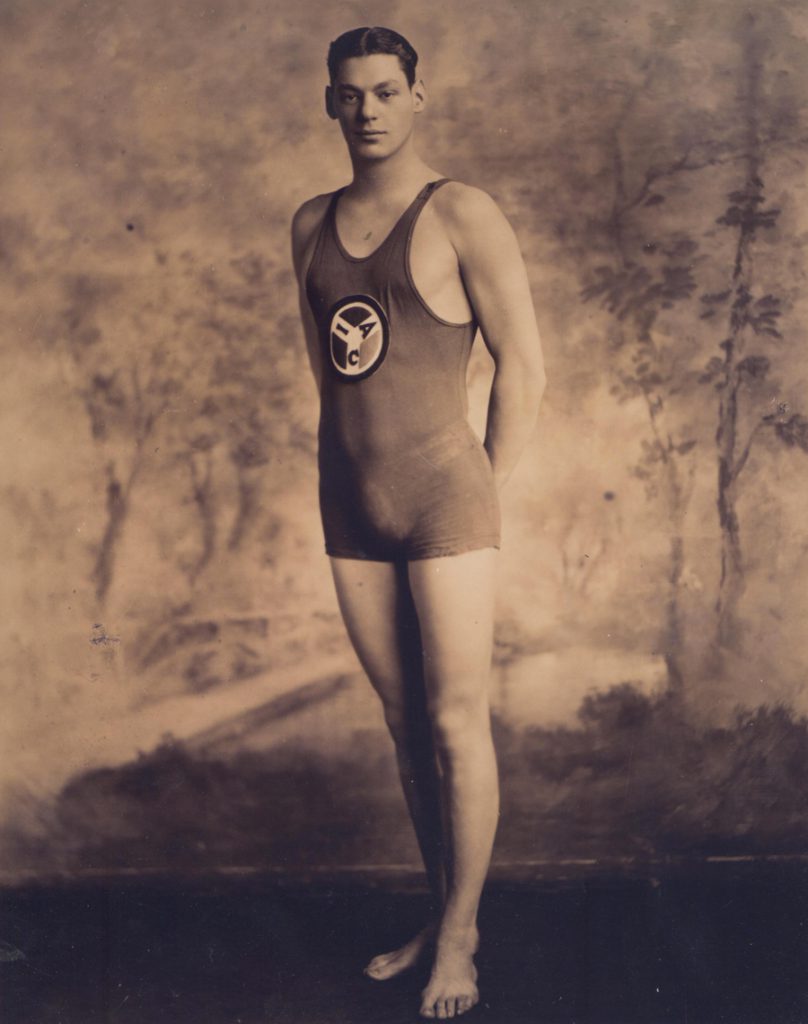

At the age of 8, his love affair with the water began with his first swimming lessons at Fullerton Beach on Lake Michigan. In the next few years he entered and won all of the races he could that were sponsored by the city. He joined the Northside YMCA at the age of 11, lying about his age to gain entry as 12 years old was the minimum. He swam there until he was 14 and won all of the swimming races as well as being a champion at running and high jumping. As these early years passed his swimming skills started to draw attention, and the assistant coach from the Hamilton Club recruited him for a few months. He told Johnny that he should be training at the Illinois Athletic Club (IAC), one of the best swim teams in the country.

In 1920 Johnny was working as a bellhop and elevator operator at the Plaza Hotel and longed to join the IAC. Through a friend on the swim team, in October he finally got a tryout with famous coach Bill Bachrach – who had already heard plenty about him. Impressed with Weissmuller’s raw talent, he enlisted him as his protege. Bachrach recounted:

“He had the gawkiness of an adolescent puppy. Also, the stroke he used was the oddest thing I ever saw… but the stopwatch told it all; nearly record time. By he time he got out and dried off, he was an official member of the Illinois Athletic Club.”

Bachrach would also serve as a father figure and mentor throughout Johnny’s life.

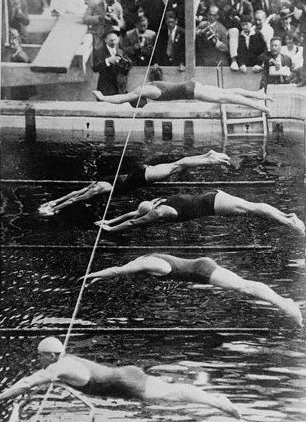

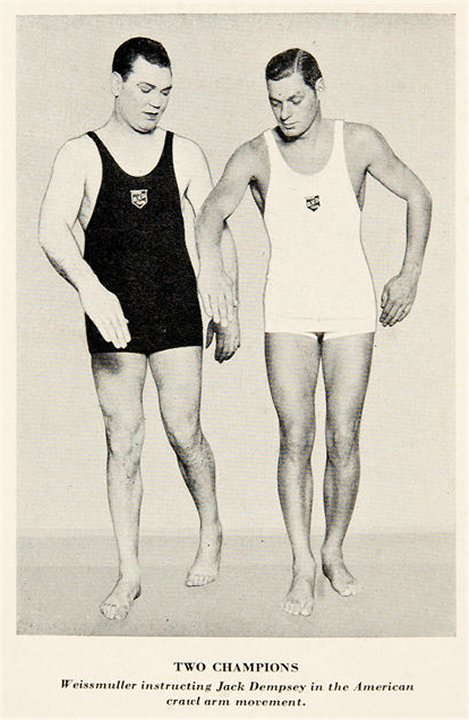

They worked tirelessly on his technique for nearly a year, integrating some of the best stroke and kick methods from the top swimmers at the time and improving upon them with Johnny’s own style and natural talent. And thus he developed his innovative version of the American crawl stroke, a sort of “hydroplaning” that allowed him to travel much higher in the water than his competitors.

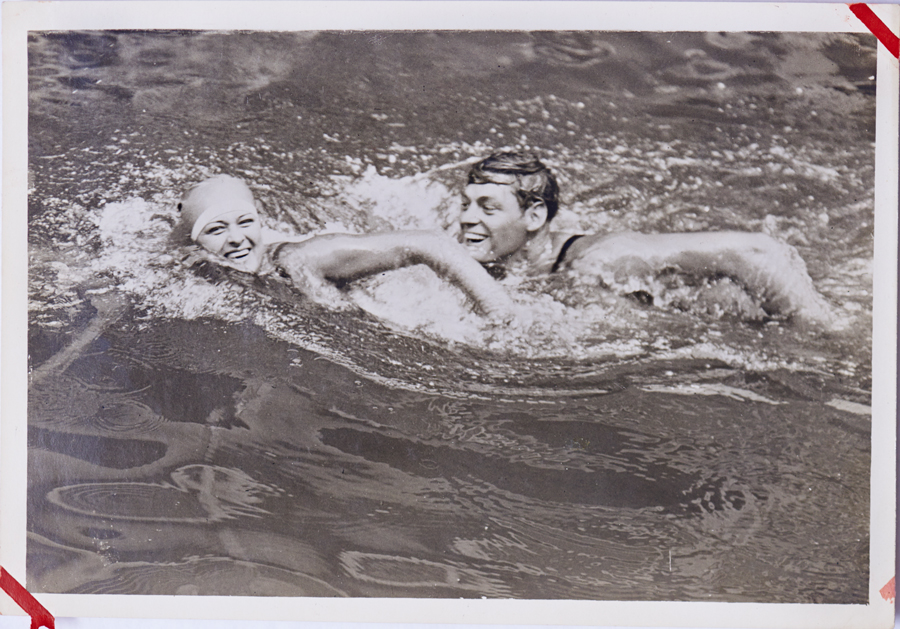

Johnny working on his kick. Watch Johnny in action here

August 6, 1921 marked his official debut in competitive swimming; he won all 4 of the Amateur Athletic Union races he entered. A few weeks later, on September 27, 1921 he set his first 2 world records at the A.A.U. Nationals meet in Brighton Beach, NY – in the 100m and 150yd events.

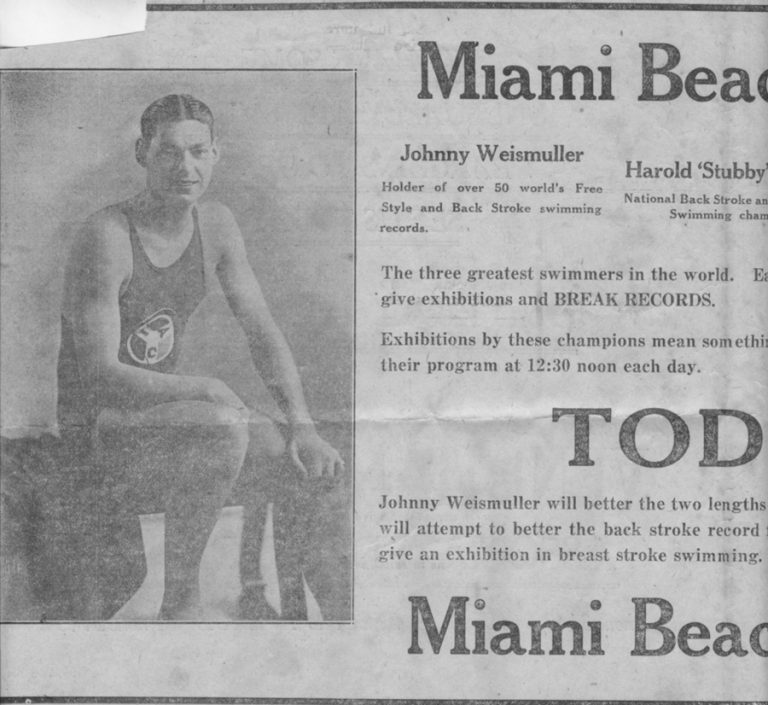

On July 9, 1922, Weissmuller became the first person ever to break the minute barrier in the 100m freestyle, clocking in at 58.6 seconds and breaking the old record of 1:00.4 by nearly 2 seconds – a huge milestone in sports achievement. He broke the mark again in 1924, clocking in at 57.4; a record which stood for nearly 12 years, to this day an unparalleled feat. And, on June 23, 1922 Johnny set a 100 yd open water time of 52.8 sec that stood for many decades thereafter.

In 1922 alone, he won 9 National Championships, in events ranging from 50 yards to the pentathlon (5 swimming/diving events) and set 24 official world records. Throughout his career, Johnny would often set several records in one day, sometimes competing in multiple events – as many as 5 – and winning them all that day.

Starting then and for the rest of his amateur swimming career, coach Bachrach and the IAC team traveled with their star Weissmuller to many US cities for exhibition meets and swimming competitions; he was usually gone from home for about half of the year.

By 1923 he already held most of the world’s swimming records in distances from 50 meters to 500 yards; that year he added 9 world records, and 15 new American records, and continued his total domination of the sport.

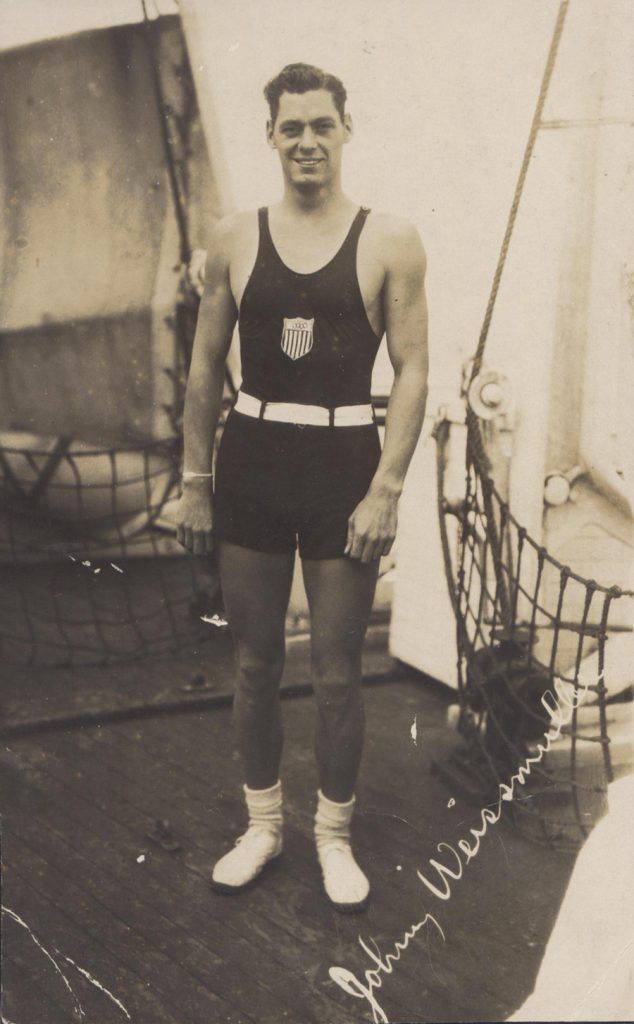

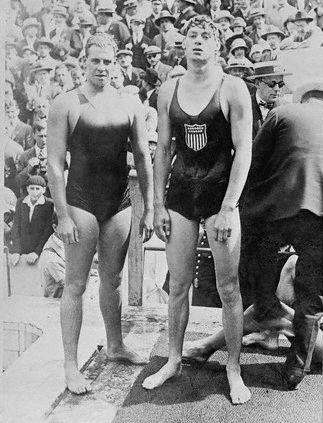

At the 1924 Paris Olympics he won 3 Gold medals for freestyle: in the 400m and 100m individuals and the 800m relay, and a Bronze medal for water polo. He’s still number one on the list of Olympic gold medalists to have medaled in two sports. He was also given a special commendation and medal for athletic excellence by French President Doumergue.

The hotly contested 100m race with rival Duke Kahanamoku (previous Gold medal winner and father of surfing) and the 400m contest (with international greats Arne Borg and Andrew Charleton) are still considered two of the greatest races in swimming history.

In Paris his feats and charisma, combined with the comedic diving routines with pal Stubby Kruger he performed for the crowds of 10,000 plus between events, helped make him the breakout star of those Olympics. And thus he became one of the world’s first superstar athletes, as these were the first Games to be widely covered by an international press corps of more than 1000 journalists.

“Clearly, everyone agreed, Johnny Weissmuller was the star of the 1924 Olympic Games. For the first time a swimmer had stolen the show from all other great athletes. He had his place in history; everyone knew that.” (from the book “Young Olympic Champions”).

Right after the 1924 Olympics, Weissmuller and Bachrach traveled Europe staging exhibitions, securing Johnny’s status as an international phenomenon. Another honorary medal was bestowed by the King of Belgium. Because of the tour he did not get to share in the hero’s welcome the returning US Olympic team enjoyed. He did, however, get a citation from and private audience with President Coolidge upon his return.

He continued his unprecedented dominance of the sport for the next two years. And in 1925, while on tour in Los Angeles, he got his first taste of Hollywood when he was invited to spend the day at Pickfair, the legendary home of film idol Douglas Fairbanks. Johnny and diver Stubby Kruger were photographed by Fairbanks and friends, who sent him copies that he kept in his personal scrapbook.

In 1926 Weissmuller entered and won the 3.2 km Chicago River Marathon, establishing his dominance as an ultra long distance swimmer as well. He also won it in 1927, breaking the record for the event.

He continued to set world and national records for and win all events he entered over the next two years – including a much publicized 51 seconds flat for the 100 yard freestyle that stood for 17 years until 1944. This is even more remarkable considering that this freestyle distance is the event swum more often than any other in the sport.

He was also a member of the 1927 National Championship Water Polo team.

On July 28, 1927 Johnny became an actual real-life hero. While training for the Chicago River marathon on Lake Michigan he and his brother saw that the passenger steamboat Favorite had capsized and started sinking. They pulled over two dozen people from the wreckage, and of those 11 survived. He was given the key to the city of Chicago for his bravery. Still shaken up from the experience, he nonetheless won the Marathon race only two days later.

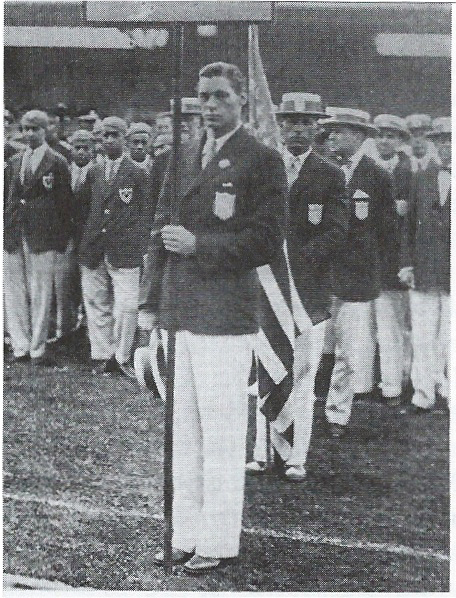

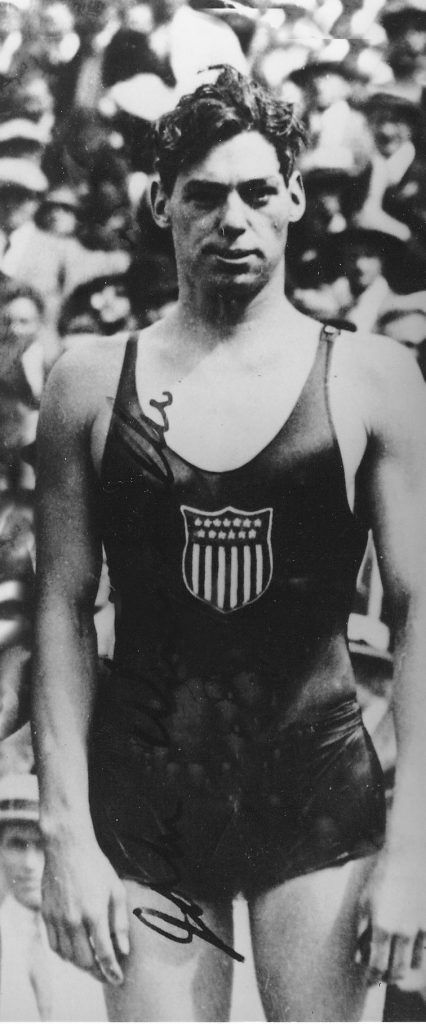

In 1928, Weissmuller was a bona fide celebrity athlete as he returned to the Olympic Games that were held in Amsterdam. He led the U.S. delegation as standard bearer in the Opening Ceremony of over 4000 athletes, alongside General Douglas MacArthur. Johnny considered this to be one of the proudest moments of his life. He won 2 Gold medals in swimming, the 100m individual and 4x200m relay; he would surely have won the gold for the 400m event but was forced by his coach to sit it out in order to play on the ill-fated water polo team.

A happy Johnny at the 28 Olympics.

At the Games, he got a special award for athletic excellence from Queen Wilhelmina of Holland; upon his return to the U.S. he received his second presidential citation, a special commendation from New York governor Smith, and the keys to New York City given to him by the mayor.

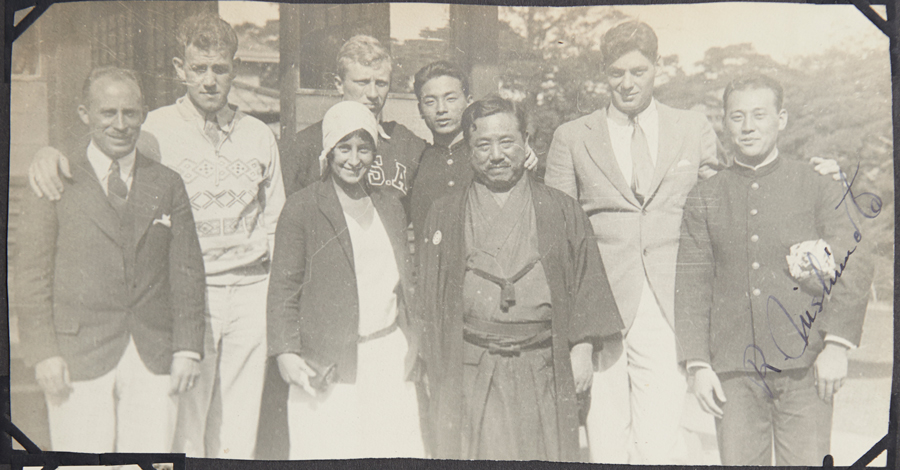

In October he was invited to Japan by Crown Prince Chichibu as part of a special swim meet in honor of his wedding. While he was there they offered him the position of head coach for the Japanese national swim team, which he graciously declined. (Read More about this story here)

Johnny swam in his final meet on January 3, 1929, after which he formally retired from competitive swimming. He cited the need to earn a better living, something that at the time was impossible for amateur athletes still competing.

From the official press release: “After dominating the amateur aquatic world for eight years or more, Weissmuller retires undefeated. With few exceptions, he holds all freestyle records in pools of all sizes in distances from 50 yds to 500 yds. Coach Bachrach says he could probably go on indefinitely breaking records and winning titles, but “you can’t earn a living and stay an amateur athlete”.

Weissmuller’s accomplishments as a swimmer stand unmatched and his margin of superiority over his rivals has been rarely seen in any sport. He retired with 67 world records (51 for individual events), 52 national championship gold medals, and his record of 38 individual US National titles stood until the 1980’s. As impressive as those numbers are, he broke world records many more times and never even turned in the record applications; this because it was often done outside of formal competitions.

He was very celebrated throughout his swimming career; his achievements were regularly reported on the front pages of newspapers in America and then worldwide after 1924. The public was fascinated by Johnny’s unbeaten streak, and every time he swam people would grab the sports section to see if he had won again. Staying at the top for nearly a decade, he had built a huge international fanbase. The combination of being such a winner and a charming, humble guy made him immensely popular.

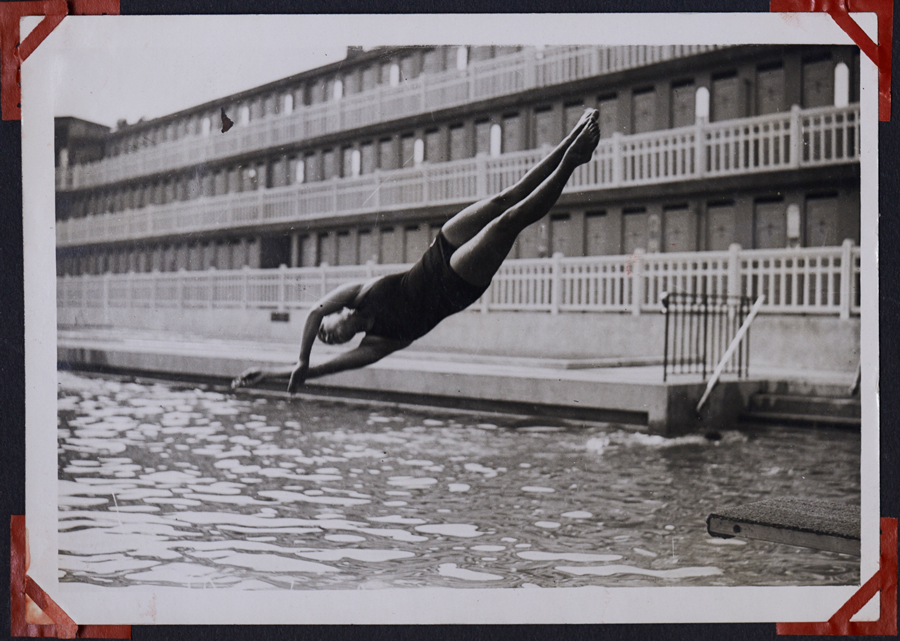

He was also an impressive diver, and though he did not compete in diving events except in the AAU pentathlons, he performed in innumerable diving exhibitions and big water shows throughout the years.

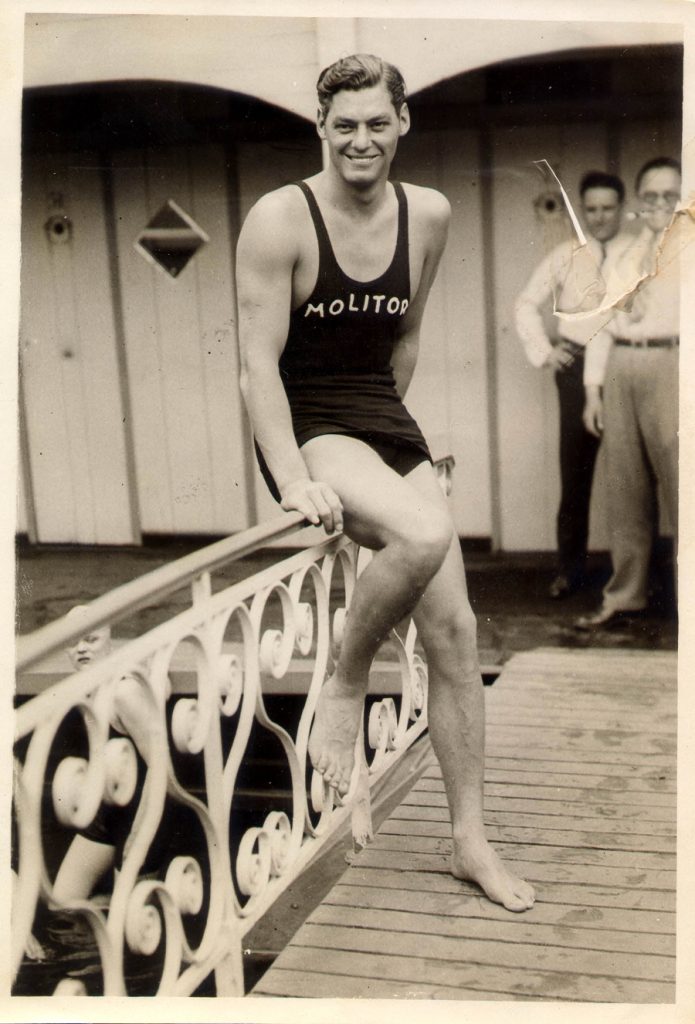

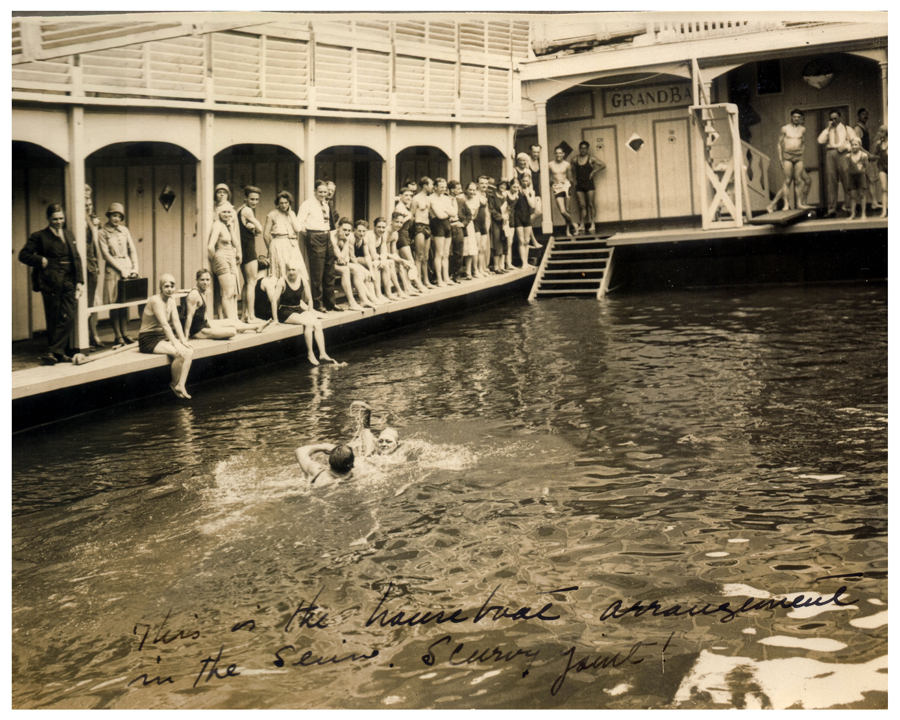

Right after retiring from amateur competition, he spent some time at the famed Piscine Molitor in Paris. After inaugurating it he worked as a lifeguard, teaching and giving swimming and diving exhibits. (The character in the “Life of Pi” was actually named after the Molitor Pool, and the book even mentions Weissmuller).

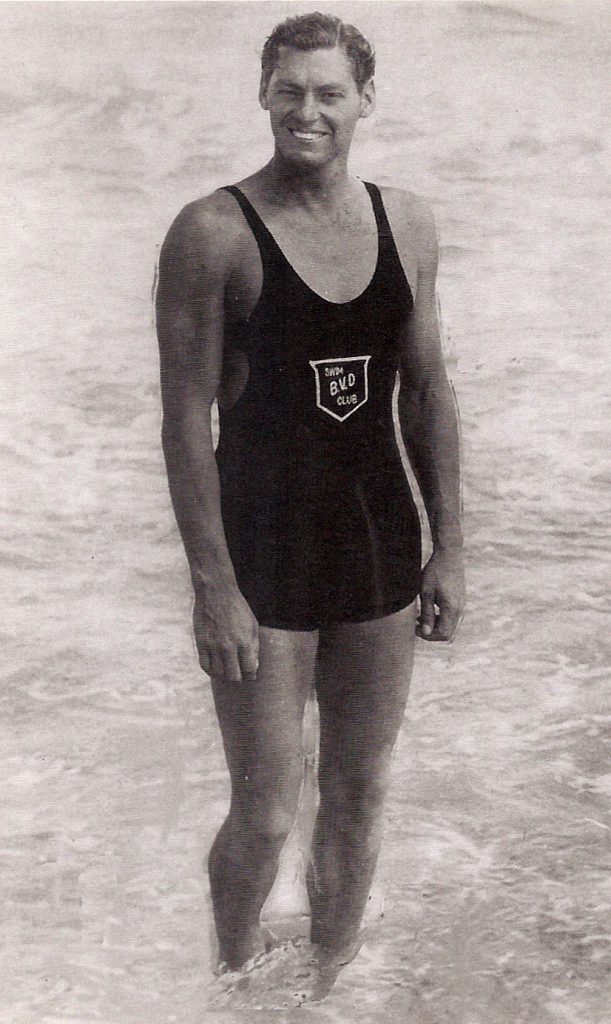

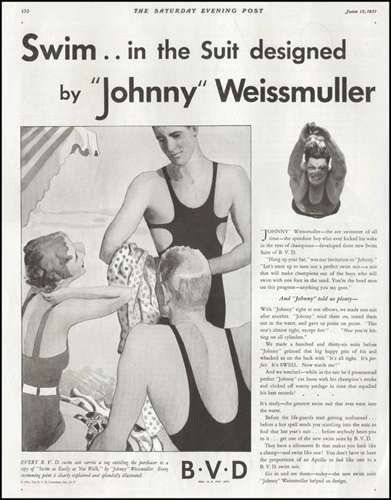

With coach Bachrach’s help, Johnny then signed an endorsement deal with BVD to model and promote their swimwear. For that he received $500 per week – a princely sum at the time. During his stint with them he also helped to design and launch a streamlined one piece tank suit and then the first male swim trunk. This made him one of the first sportsmen ever to endorse and design athletic wear. He appeared in many ads and toured the country as their spokesperson. He always said his favorite part of the job was running the BVD Swim Club for youth.

He also was featured on other products and in ads, even before he would soon shoot to fame on the silver screen.

While in New York city for BVD in 1929, he was spotted by a producer of the film Glorifying the American Girl, featuring the Ziegfeld Follies, and offered the small part of Adonis. However, in the end BVD didn’t agree with the use of their star so he was mostly cut from the movie. Later that year he starred in Crystal Champions, a film short that was part of the famed Sportlight series that showed in 8000 theaters in the US and more than a thousand in Britain.

“Johnny Weissmuller gave our cameras excitement during the boomtime 1920’s – in Miami and then at Silver Springs. FL, where we made Crystal Champions, a great grosser.” producer Grantland Rice

Hollywood also came calling that year, and it appeared his first major movie role would be in a new “talkie” starring Jeanne Eagels; however, shortly after production began tragedy struck when Ms. Eagels died of an overdose so the film was never made.

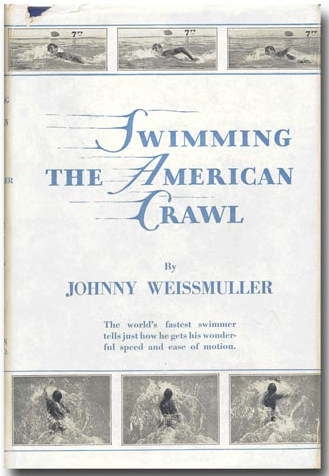

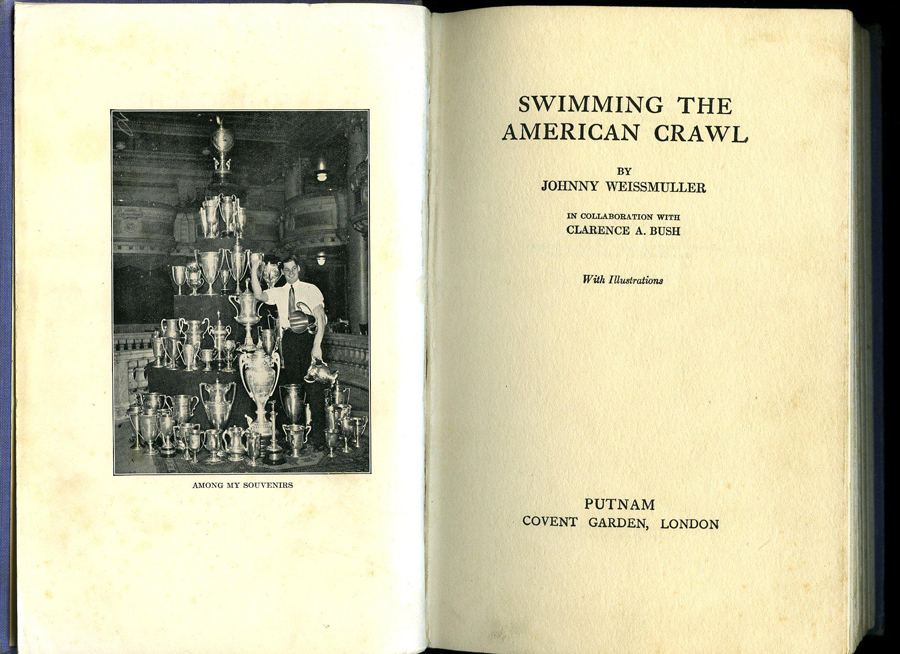

In the early part of 1930, Houghton Mifflin released Weissmuller’s autobiography “Swimming the American Crawl” (written with Clarence A. Bush). In the 190 page hardcover book with photos, Johnny detailed his techniques and recounted parts of his childhood and memories of his most outstanding swimming and Olympic triumphs. Excerpts were published in the prestigious Saturday Evening Post.

In 1931 he met and then married actress/singer Bobbe Arnst, after only two weeks of courtship. Shortly thereafter he was offered a transfer to the B.V.D. office in Los Angeles.

Later that summer, Johnny was diving and swimming his daily laps at the Hollywood Athletic Club, where a bevy of onlookers always gathered to admire him. That day, MGM screenwriter Cyril Hume was working out at the club and saw the man in the pool. Hume was at that time working on a new project, Tarzan the Ape Man, based on Edgar Rice Burroughs’ famous character. He knew that the studio had been conducting a major search for the lead, and had even spoken of 1928 Olympians like Herman Brix and Weissmuller. Upon being told he was watching Weissmuller in person, he asked him to come to MGM for a screen test.

After the initial meeting with Johnny, even before the test, the producers and director knew they had at last found their ideal Tarzan. Producer Bernard Hyman famously asked for Johnny’s name, and then said ”too long, we’ll have to shorten it”. When the others exclaimed that Weissmuller was the world’s best swimmer and an internationally famous Olympic champion, he capitulated: “All right then, we’ll just lengthen the marquee. And, put lots of swimming in the film!” Filming began on October 31,1931, and ended 8 weeks later.

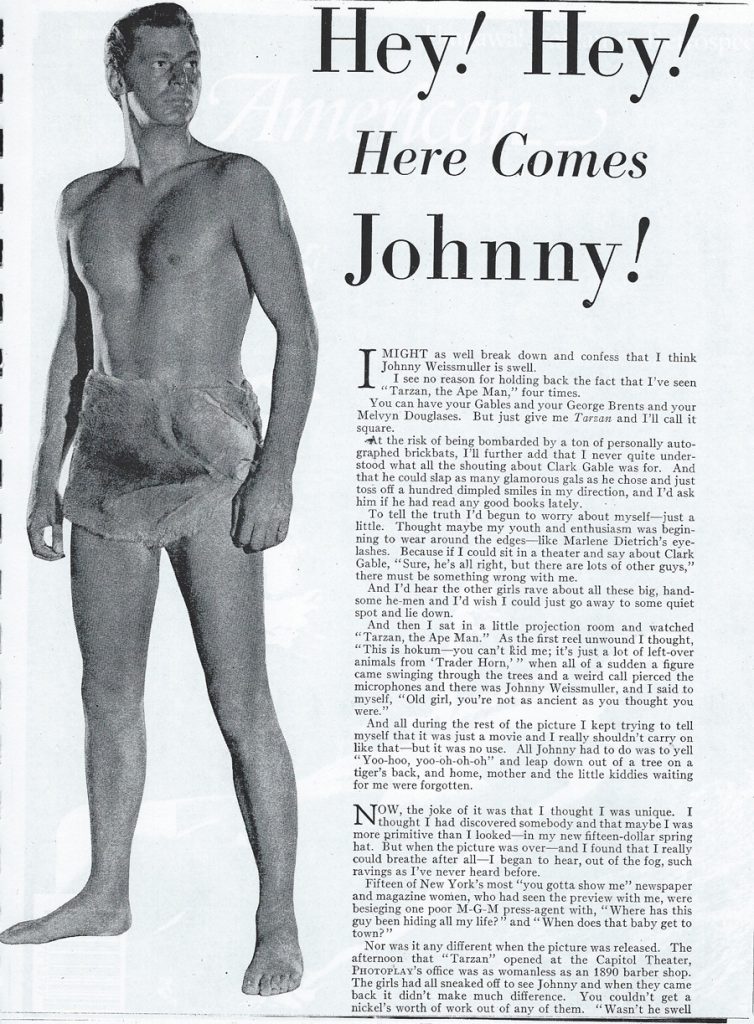

Released in late March of 1932, Tarzan the Ape Man was quite unexpectedly a huge critical and public success in the US and then worldwide; it was one of the top-grossing films that year. Johnny instantly became part of the inner circle of Hollywood film stars. (Watch the Tarzan the Ape Man trailer here)

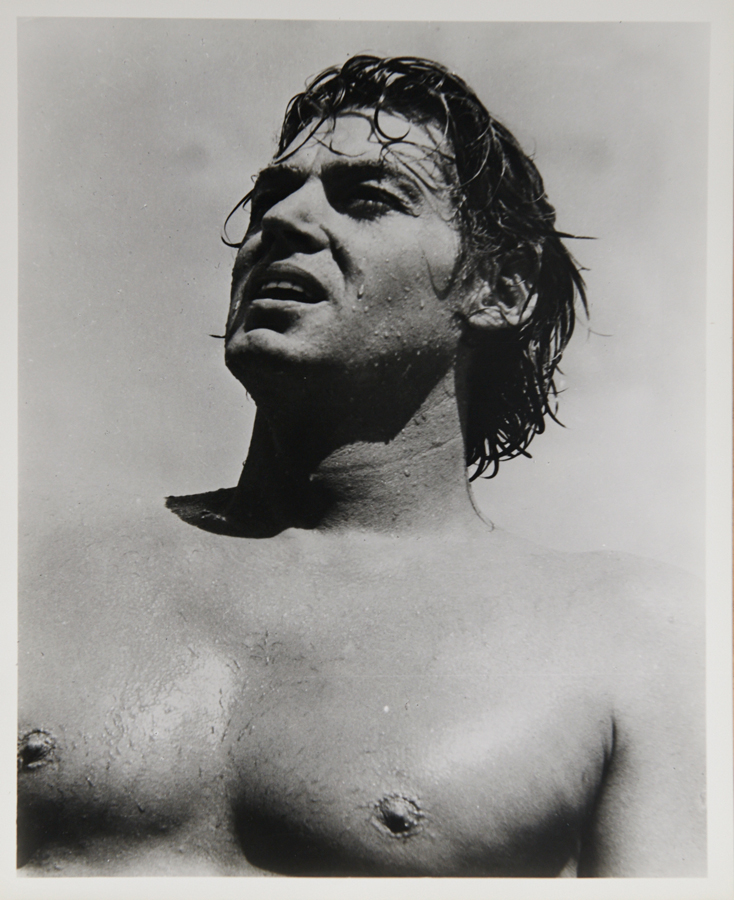

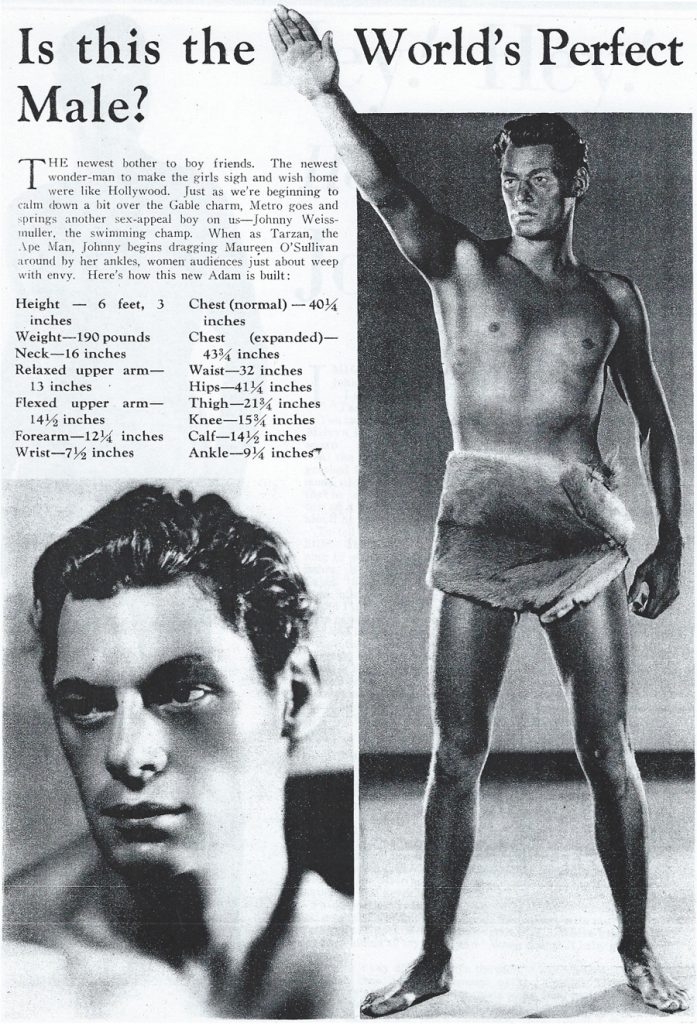

Almost overnight, he not only became “Hollywood’s latest heartthrob” but his position as the first true international male sex symbol was cemented. His flawless physique and athleticism were the subject of many articles – from film reviewers and female reporters to fitness and athletic experts.

Typical headlines were: “Is this the world’s Perfect Male?” and “Johnny Weissmuller has the World’s Finest Physique”.

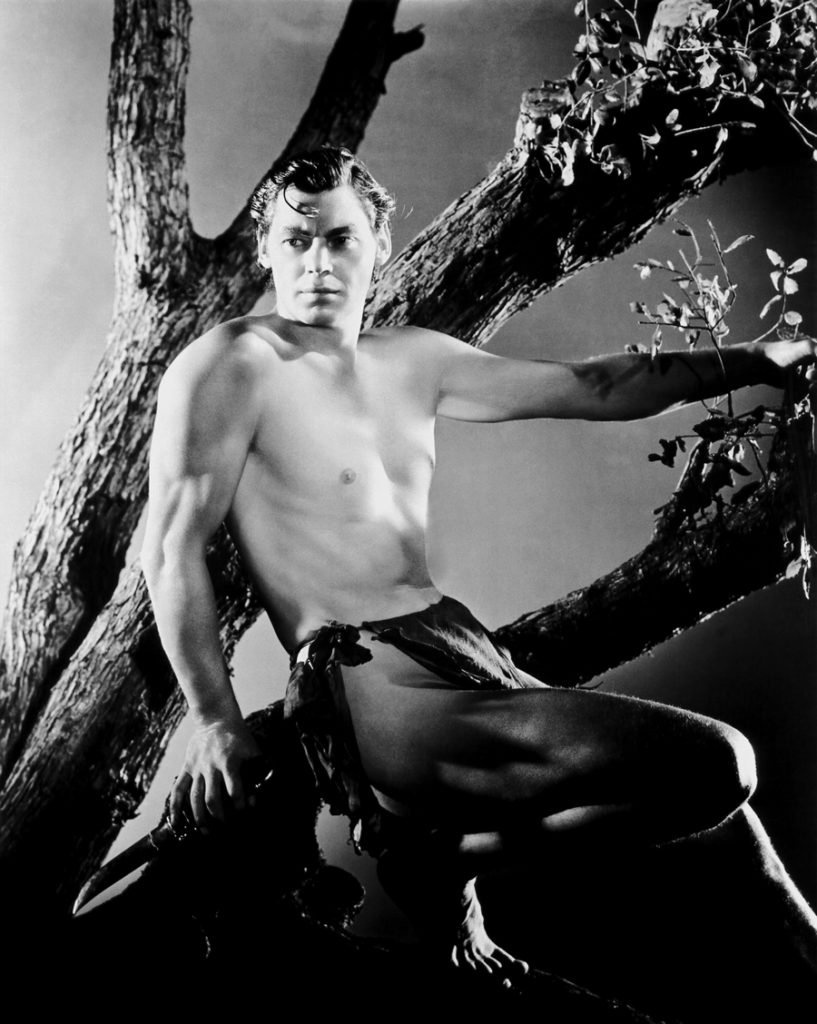

Much has been written and said about Weissmuller being from that point on and forevermore the definitive screen Tarzan. There were many factors that contributed to Johnny’s success in the role for this and the eleven more films to come…

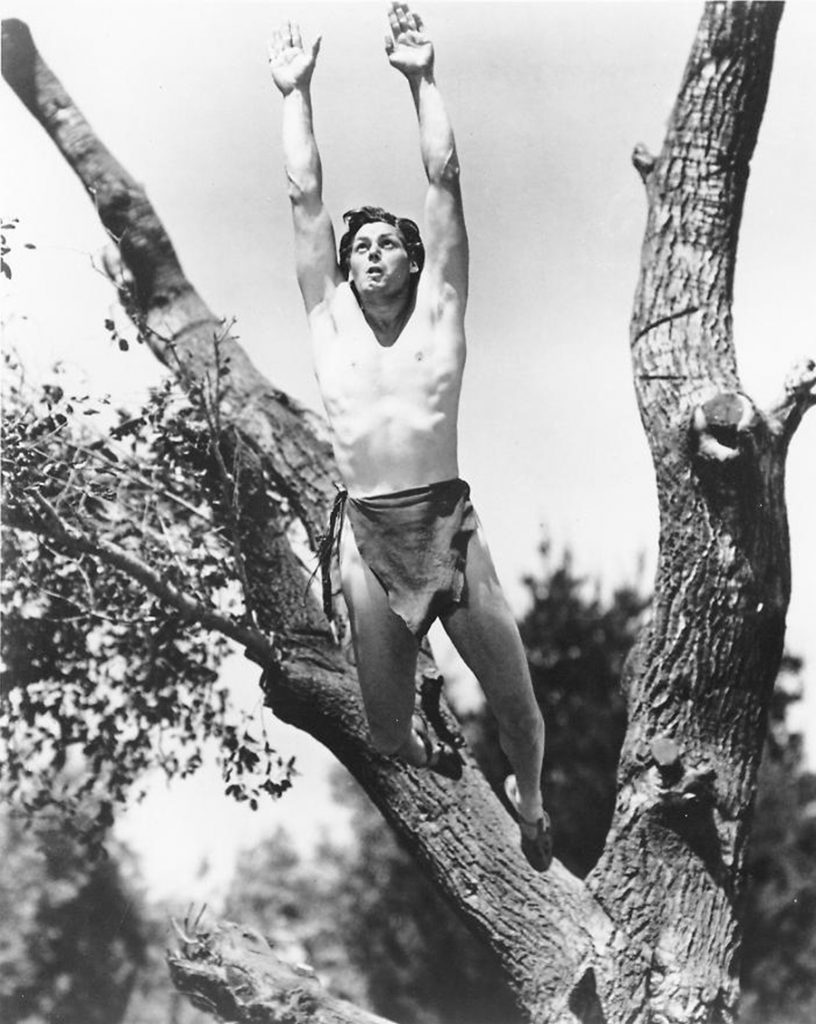

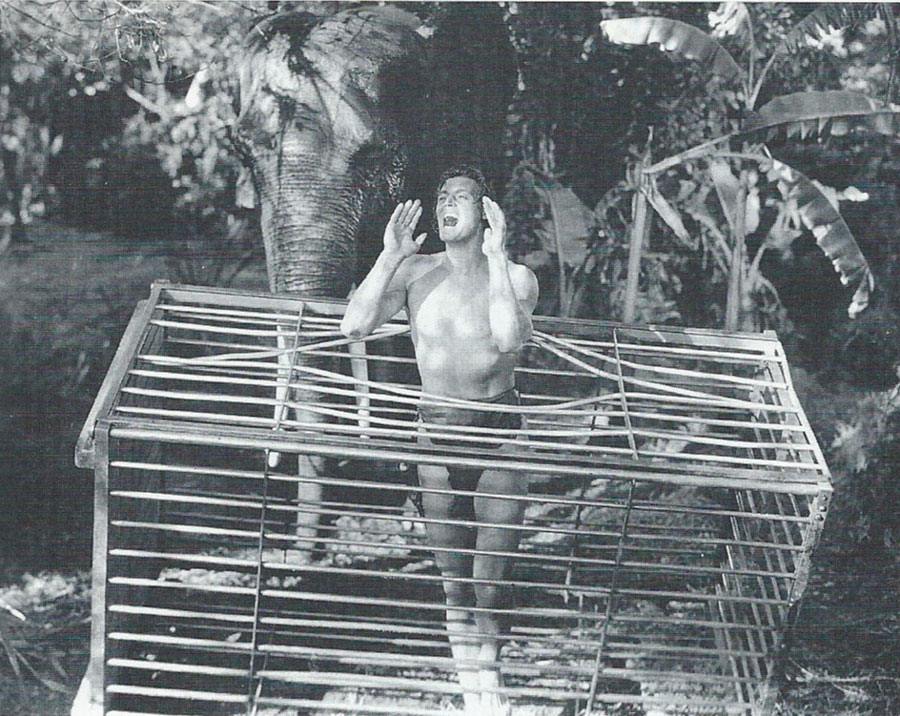

Though not formally trained as an actor, he was perfect for the role: tall, lithe and not overly muscle-bound he moved with the grace and presence of a big cat. He was totally at ease wearing minimal clothing in public from all the years of swimming stardom. And when he turned serious on camera, his brooding expression and ability to conjure an animal-like sensitivity in his eyes made him totally believable. He also possessed an amazing natural talent for comedic timing.

“The Weissmuller jungle man was simple, straightforward, lovable, strong and sensitive… (And) there were other subtle touches of an animal nature – the wariness, the quick turning of the head, and the catching of a scent.” Rudy Behlmer, Film historian and Tarzan expert

“Everything about Weissmuller was flowing, harmonious and natural. Weissmuller’s Tarzan was pure existence, a sort of degree zero transmuted onto the figure and motions of an Adonis-like man. He was the natural hero in an age of heroes with supernatural or extra-human powers. Weissmuller embodied the man whose entirely human powers allowed him to exist in the jungle with dignity and prestige. Surrounded by danger and challenge, Weissmuller was (rarely) armed with anything more than a hunting knife…” Renowned author/philosopher Edward Said for Interview magazine

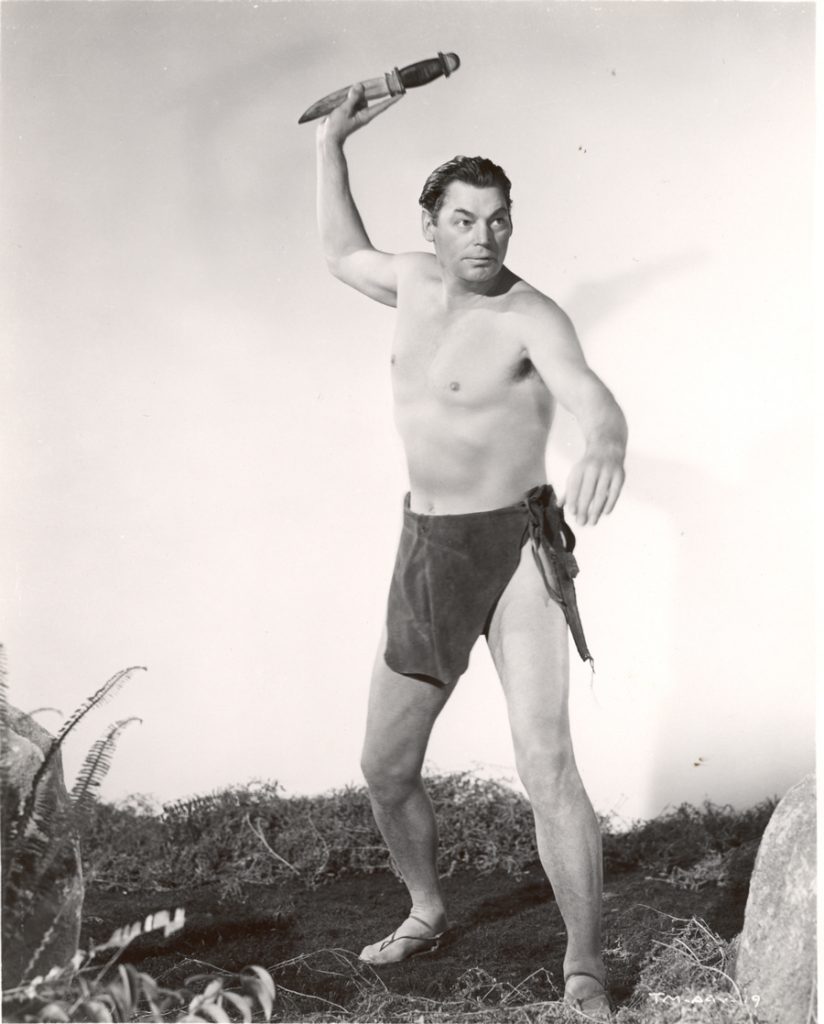

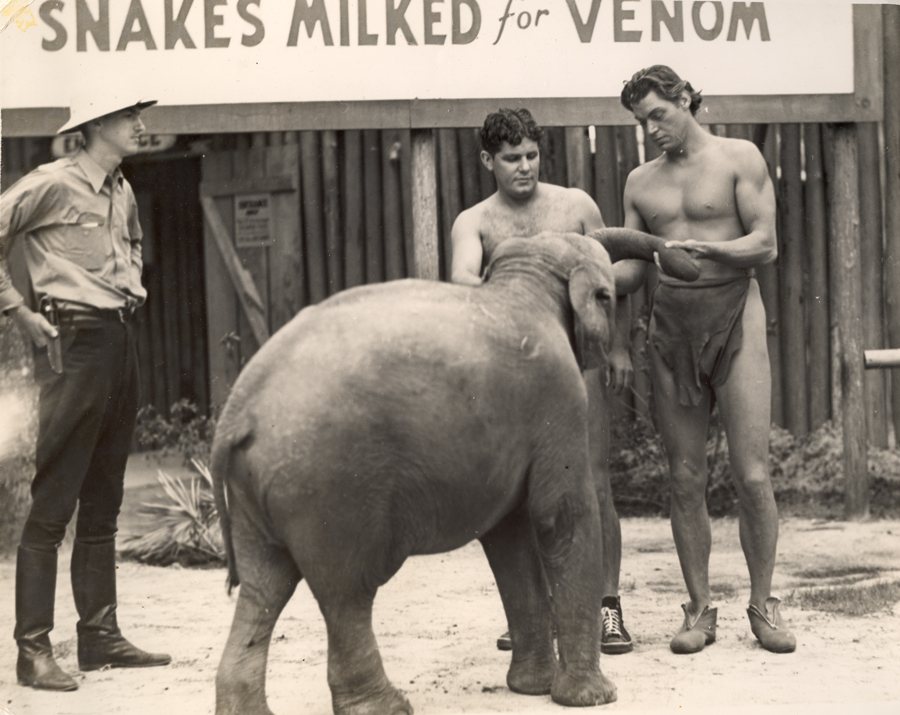

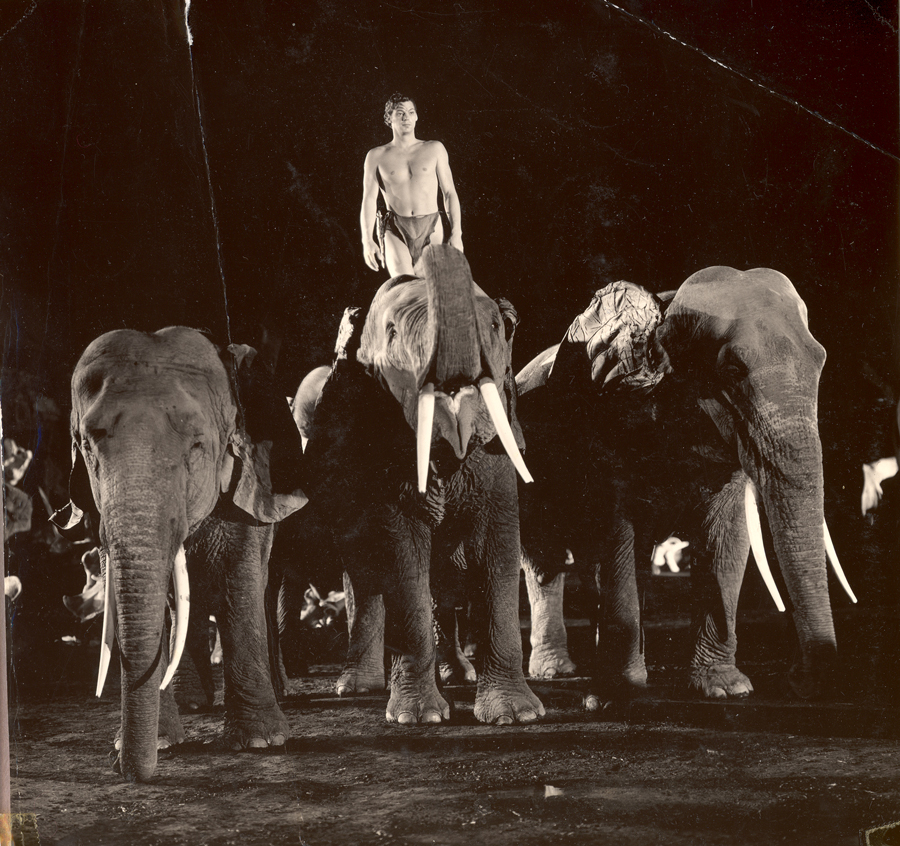

Johnny did many of his own stunts – actually riding wild rhinos and elephants, interacting with the chimpanzees and other animals, climbing trees and swimming and diving. Though stunt doubles were used for some scenes, the many dangerous stunts he did perform himself gave the pictures a realism that showed. He would always build a great rapport with the animals, including the chimpanzees that were notoriously difficult to work with. In fact, notwithstanding some uncomfortable chafing he sustained from riding Mary the rhinoceros, Weissmuller was never seriously injured by any of the animals during his seventeen-year reign as Tarzan.

A good example of the real danger he faced during the filming of certain scenes was the thrilling and famous elephant stampede at the end of Tarzan the Ape Man. It was done live and took five days to plan; very different from today’s computer generated imagery!

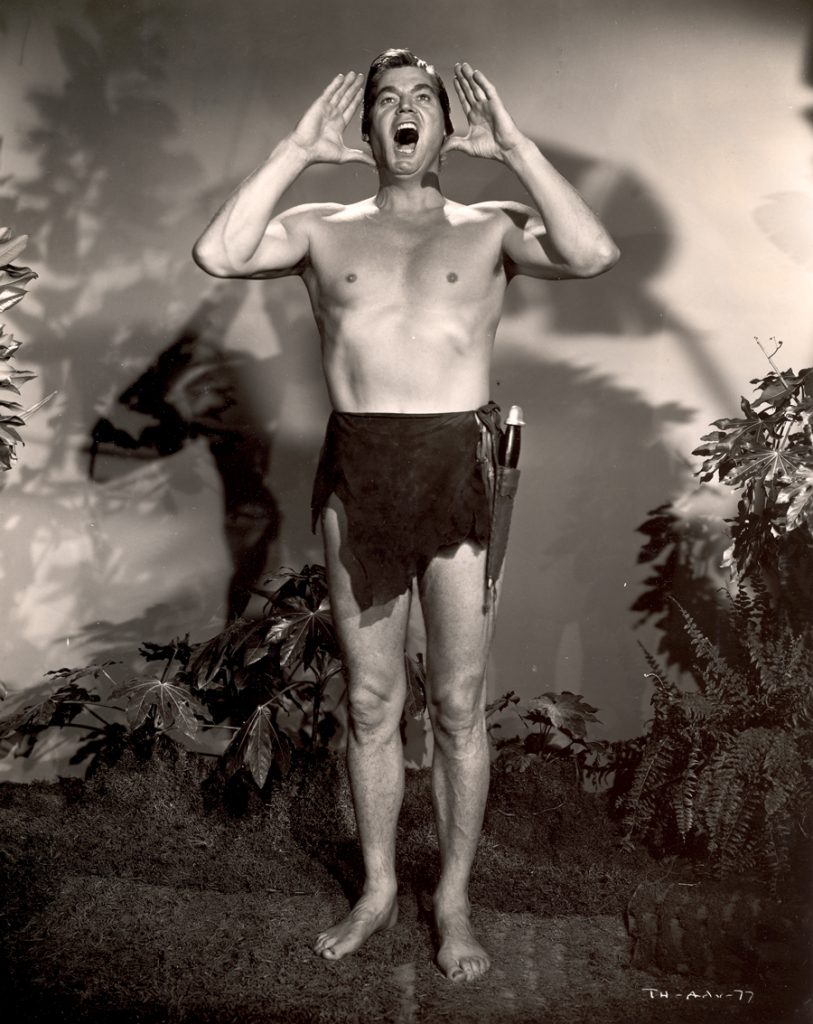

Though his voice may have been sweetened up sonically for film by MGM’s sound department, it is certain that Johnny himself originated his iconic Tarzan yell. He based it on the yodeling he learned as a boy in the German community of Chicago, and the influence of occasional childhood outings to the opera with his mother. It would be used for nearly every live action film or tv series to come, dubbed in when he was no longer the star. And to the universal delight of fans, he would easily reproduce it throughout his life and in sometimes unlikely settings – reveling in the happiness that his gesture always produced.

The Weissmuller Tarzan yell passed to legendary status and is one of the most recognizable cinema soundbites in history. (Listen to the Tarzan yell here.)

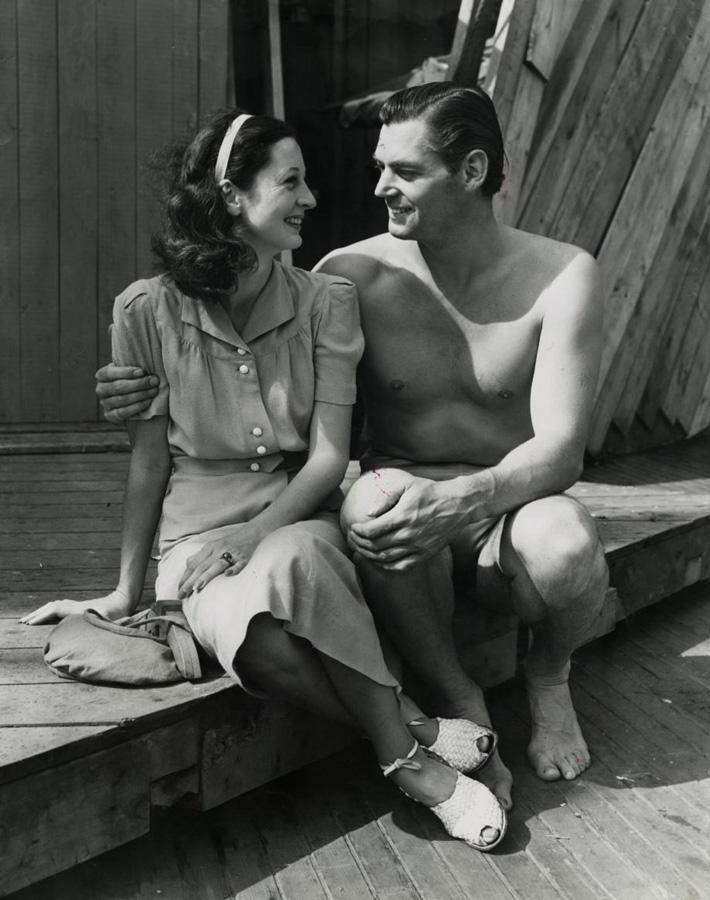

And finally, for the first six Tarzan films that were part of the MGM franchise he had Maureen O’Sullivan as his Jane. Their screen chemistry and perfect rapport were very compelling and totally believable, and they are widely considered to be one of the all-time great screen couples. They remained close friends throughout their lives…

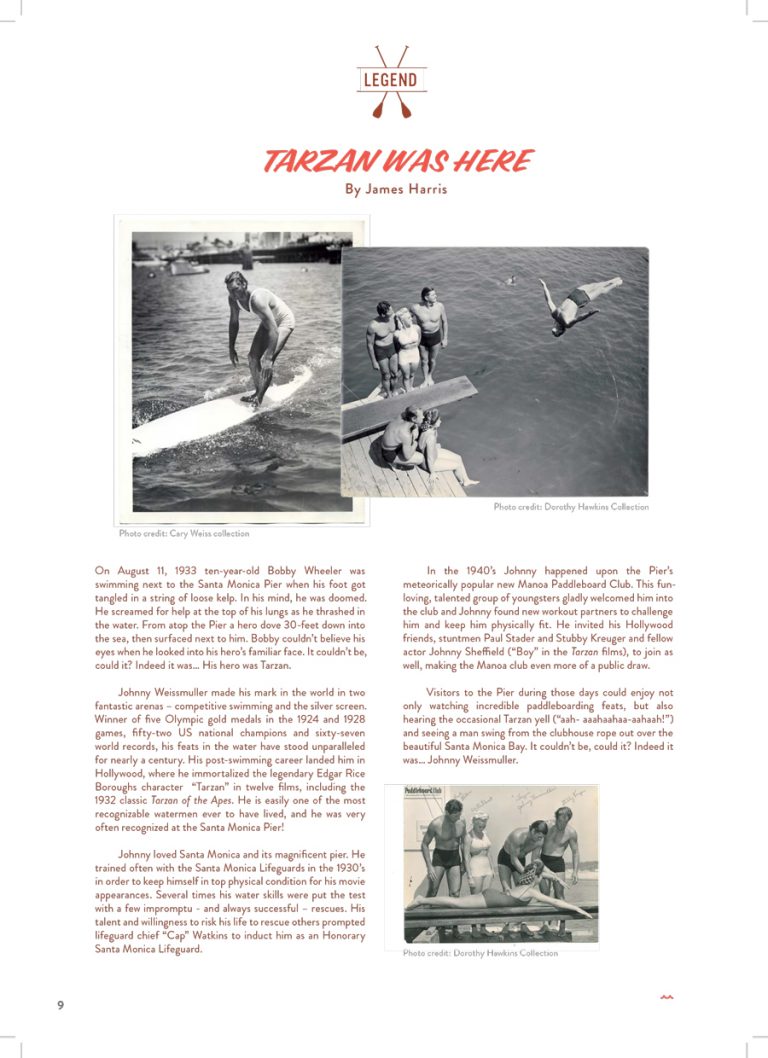

In the summer of 1933 he was appointed to the Santa Monica lifeguard squad on a volunteer basis; not a publicity stunt, he took it very seriously as he wanted to put his spare time to good use and loved being in the water. In August he made his first of many rescues, saving the life of a 12 year old boy.

He also got more into the nascent sport of surfing and was a pioneer for the early sport of paddleboarding. As a big celebrity, he did much to support and publicize these sports.

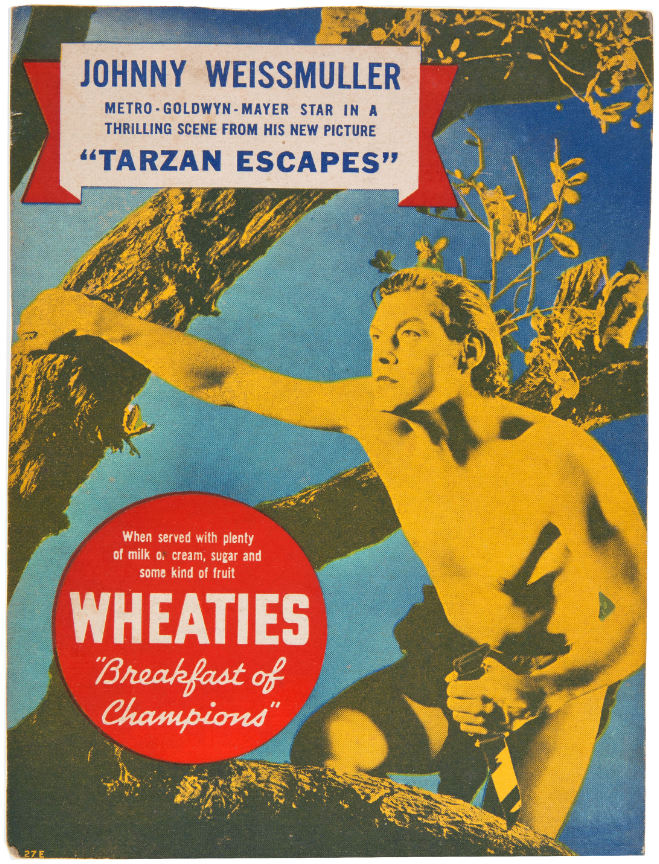

Also in 1933, Weissmuller became the main celebrity endorser for Wheaties breakfast cereal that year. He was on the box, and appeared in many full-page ads and special promotions. Another popular product he endorsed in the 1930’s was “Tarzan” bread, which one year sold 75 million loaves!

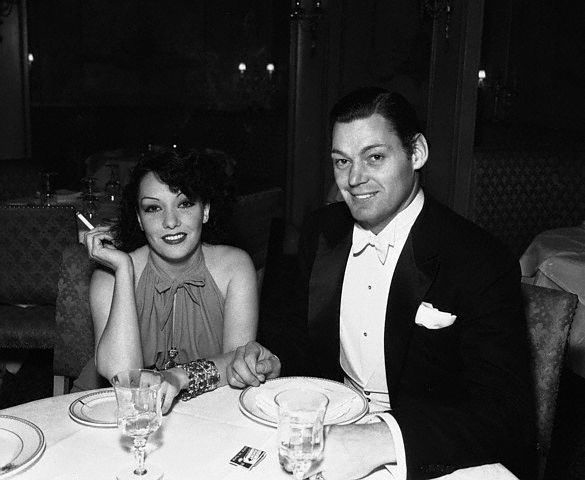

After having divorced his first wife, partially at the behest of MGM, he dated Lupe Velez, the notorious “Mexican Spitfire” and one of the first Latina film stars in Hollywood. The petite and gorgeous Lupe was well known for her sex appeal and great comedic talent, and also for her emotional instability and wild parties. Johnny later said he was a “ready-made fool” who fell madly in love with her. They married in October of 1933, and the attractive couple’s stormy marriage of five years would become part of Hollywood folklore. But their sense of style and adventurous outings also made them trendsetters in their day.

Tarzan and His Mate was released in the Spring of 1934. It is arguably the greatest Tarzan film ever made, of more than 40 throughout the years. In 2003, the U.S. Library of Congress deemed the film “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant” and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry. The American Film Institute counts the movie on a list of the greatest film love stories ever told.

It was an even bigger critical and international box office success than the first film, and firmly established Weissmuller and O’Sullivan as one of cinema’s favorite couples. (Watch the Tarzan and His Mate trailer here.)

The original underwater swimming scene (later restored for the DVD version) had a nude body double for Maureen O’Sullivan and became one of the catalysts for the strict enforcement of the film industry “decency statutes” and censor codes. It was redone with the swimmer in costume and there were actually three versions eventually released. Either way, the gorgeous underwater ballet – choreographed in part by Weissmuller – is a classic and groundbreaking scene.

In the famous underwater river battle with a giant crocodile, Johnny himself was grappling with the huge mechanical reptile; however, in other films he would go on to wrestle live alligators, working in a tank of frigid water to make the beasts lethargic. And one of the most exciting scenes ever made for any Tarzan film was Johnny riding on the back of an African rhinoceros. Another of the most iconic screen Tarzan images is taken from a scene in this movie, where Weissmuller is standing atop the lead elephant of the herd called by Tarzan to surround the elephant graveyard.

Finally released at the end of 1936, the third film Tarzan Escapes was roiled by production changes and repeatedly delayed by the studio. MGM wanted to be sure that it would far outshine the two low-budget, unsuccessful Tarzan films made without Weissmuller that were released in the intervening time. Though perhaps not a true classic in the way the first two films were, the worldwide public loved it and it was a hit. And it made certain that by that time anyone other than Weissmuller was considered to be an imposter in the role.

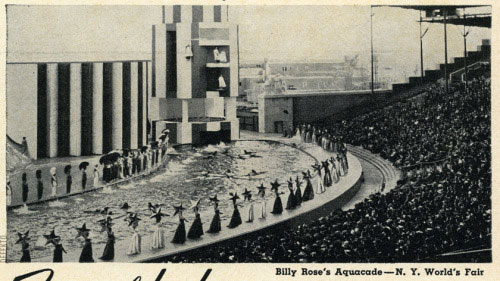

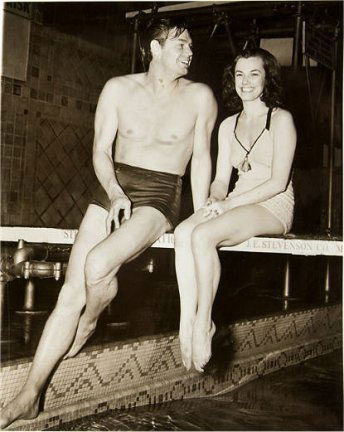

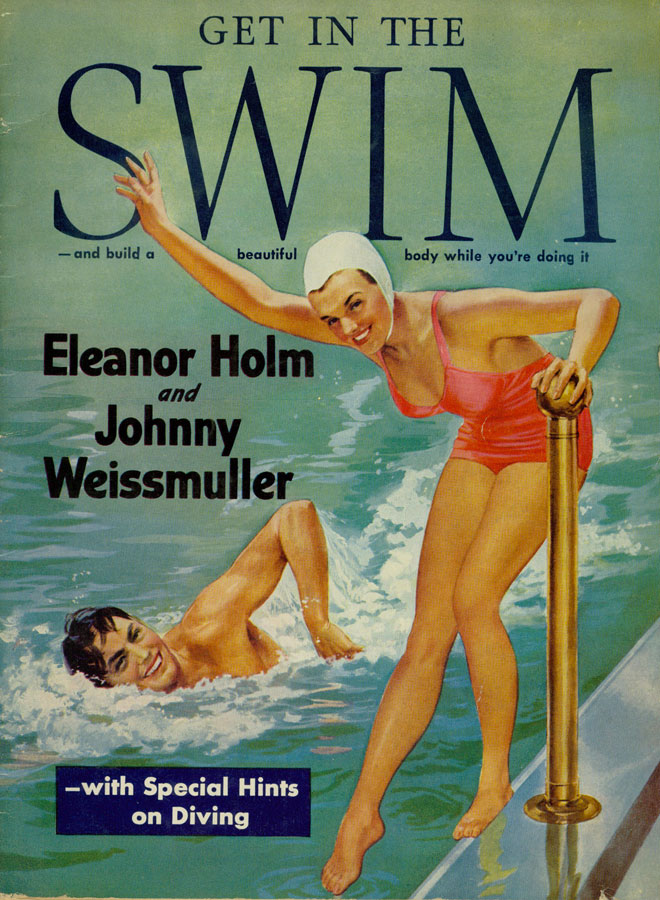

While he was under contract at MGM, they never allowed Weissmuller to be lent out to other studios or to play any other role. But they did consent to him starring in occasional swimming exhibitions and the water shows he loved to do, as long as they were big ticket events. The first major one was Billy Rose’s Aquacade at the 1937 Great Lakes Exposition in Cleveland, in which he starred with fellow Olympic champion and dear friend, the lovely Eleanor Holm.

The pair went on to headline an even larger Aquacade extravaganza at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Several million people attended the Aquacade that summer, and Billy Rose became a rich man because of the huge success of the show. Johnny wore gold swim trunks to highlight his gorgeous physique, and performed magnificent dives and swimming. Weissmuller was still in such superb condition at the age of 35 that he was able to easily beat the current national champion of the 100yd freestyle in a practice race in NYC that summer!

Slated to star again in the new Rose Aquacade at the San Francisco World’s Fair in 1940, Johnny helped to choose from the five finalists of the more than 75 young women who had auditioned to be featured as his partner (Holm was to remain with a revival of the NY show). He picked 17-yr old swimming champ Esther Williams. Her performances with superstar Weissmuller, and his introducing her to the MGM studio heads, helped to launch her own path to film stardom.

In the summer of 1938 formal divorce proceedings from Lupe had begun, and were finalized in August of 1939. However, they remained good friends and when she passed away from an overdose five years later Johnny was a pallbearer at her funeral. He had been her only legal husband, and was deeply saddened by her premature death.

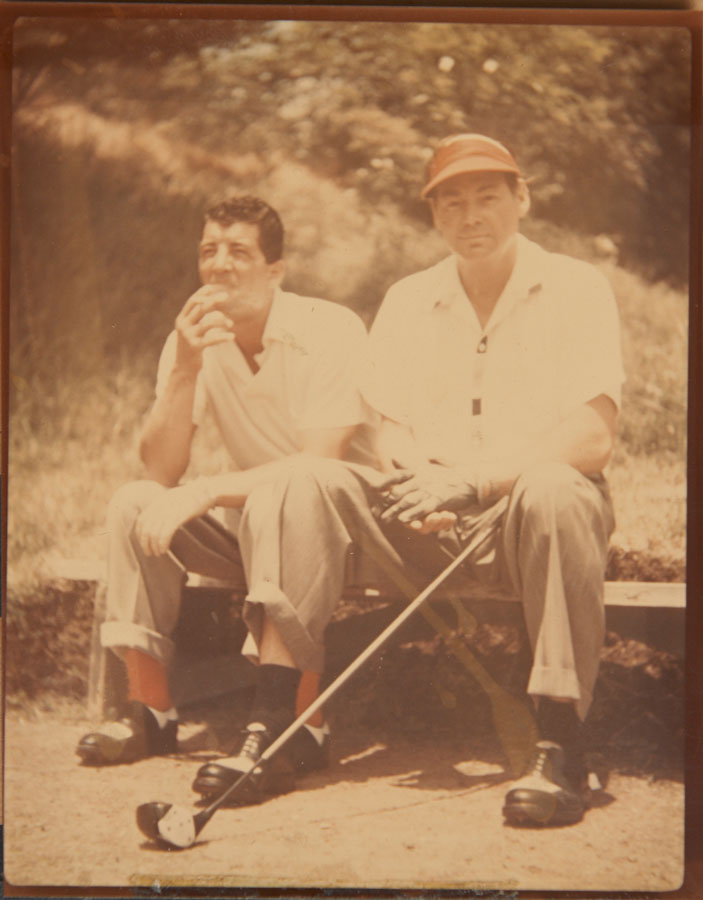

Weissmuller was an avid golfer for much of his life, having started back in the 1920’s at the IAC. He was one of the top celebrity golfers in the country for many years, and helped to establish major tournaments like the Bing Crosby Pro-Am Classic (Crosby was an old pal by then). He was very proud of the 5 holes-in- one he hit over the course of his golfing career, and the sport played a big role in his social and athletic life from the 1930’s until his later years. (Read more about this story here.)

In the Spring of 1938, he had met Beryl Scott, a 21 year old San Francisco socialite, during a golf tournament at Pebble Beach, CA. Johnny and Beryl were married on August 20, 1939, only days after his divorce was finalized. Although they turned out to be incompatible from early on – with the pressures of being wed to a big movie star certainly contributing to the discord – having kids was a priority for both of them. And so Beryl would go on to bless Johnny with his only three biological children: John Scott, Wendy Ann and Heidi.

Meanwhile, in 1938 MGM had been conducting a widespread search to find the boy who would play Tarzan’s son in the next film. Hundreds of young boys were screened for the role. Finally, Weissmuller gave his personal okay on the selection of Johnny Sheffield. He had taken a liking to him at the interview, and ended up teaching him how to swim once he saw that Sheffield was not afraid of the water. “Big John” (Weissmuller’s nickname) developed a strong bond with “Little John” (as he came to be called), and they were very close during the decade they made their eight Tarzan films together.

Tarzan Finds A Son! began filming in January of 1939, and was released in June of that year. It was another great success in the U.S. and abroad. Choosing it as “movie of the week” Life magazine expressed the majority opinion: “By the addition of a young boy to the Tarzan family, the future of the series seems assured.” Apparently MGM also felt that way, as they extended and upgraded Weissmuller’s contract.

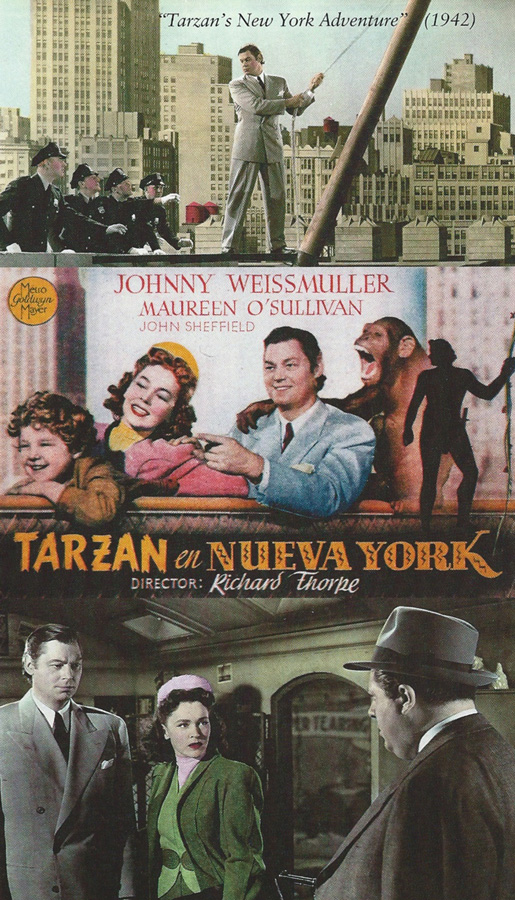

The last two MGM films were Tarzan’s Secret Treasure (1941) and Tarzan’s New York Adventure (1942). The first was especially noteworthy for the fact that it featured a young black actor in the role of a native lad suddenly orphaned, who becomes a part of the Tarzan clan for this story. It was revolutionary at the time to portray a mixed race family and friendship in this way. And, Johnny personally always championed the cause of all minority actors and rights when he could.

Tarzan’s New York Adventure was the only Weissmuller Tarzan film in which he appeared fully clothed. Though decidedly different than the previous films, most critics saw it as a refreshing change of pace; it was a fan favorite and has become a cult classic. It provides many humorous and touching scenes as Tarzan interacts with “modern society” and really highlights Johnny’s comedic talents. He also did many new and dangerous stunts in the picture, including climbing high up on the actual Brooklyn Bridge.

As World War II loomed and then overtook America and much of the world, Johnny wanted to do more than just be a cinema hero and source of enjoyable escape to a beleaguered nation. During those years he did as much as he could to help the war effort by participating in innumerable celebrity fund-raisers and shows for the troops, including being part of the famed Hollywood Canteen (about which the film Stage Door Canteen was made in 1943). He also spent a lot of time visiting with wounded and disabled veterans at VA hospitals nationwide.

Twice a month for 2 years he intensively trained troops in dangerous operations like swimming out from under and diving into water covered with flaming oil, at the Long Beach Naval Academy in California. And – indicative of his already great influence on popular culture – at times during the War homesick soldiers asked for the Weissmuller Tarzan yell to be broadcast to them at the battlefront for inspiration.

The war not only had major repercussions for the country and the world, it also severely compromised the motion picture industry. And for the Tarzan films, three quarters of their revenue came from markets outside the U.S.; so, MGM made the decision to not make any more Tarzan pictures. But producer Sol Lesser of RKO had been waiting for the chance to work with Weissmuller as the star of his favorite franchise, and so immediately bought out the rights to the character and offered Johnny a contract. He also retained Johnny Sheffield as Boy; Maureen O’Sullivan took the opportunity to retire from acting for a number of years.

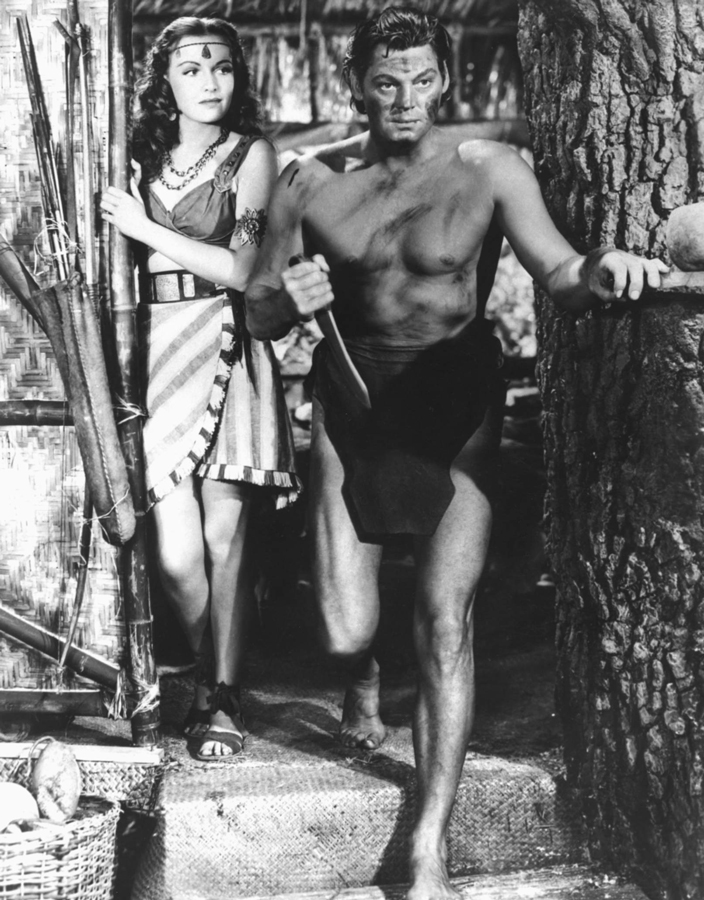

Johnny went on to make six Tarzan films for RKO Pictures in rapid succession, starting with the 1943 release Tarzan Triumphs. Although they were lower-budget than the MGM movies, there were several noteworthy and acclaimed adventure films in the bunch and they became a solid part of the Weissmuller Tarzan legacy – especially the final three films. They had a totally different aesthetic and pacing than the earlier films. Some were set in contemporary times (e.g., battling the Nazis) and some practically in fantasylands, and they were filled with lots of strong, exotic women. Loved by the public, they endured the test of time and some iconic images of Weissmuller as Tarzan come from those years.

After the first two pictures, in 1945 RKO brought Jane back in the form of Brenda Joyce, a tall beauty with strawberry blonde hair. Johnny jokingly said about the change: “I don’t know what the kids are going to think when they see me with a blonde Jane; kind of looks like Tarzan’s been playing the jungle a bit.” She proved to be a popular choice as the new Jane.

And Johnny was as popular as ever as Tarzan, receiving thousands of letters each week from fans around the globe.

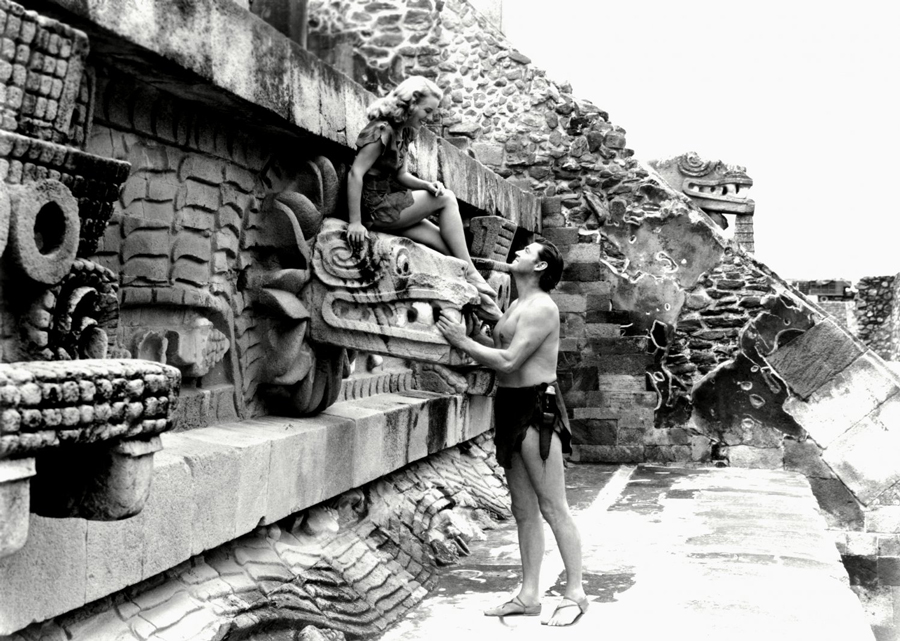

Tarzan and the Mermaids, which turned out to be Johnny’s last appearance as the Jungle Lord, was shot entirely on location in Mexico. It was an action-packed adventure that featured spectacular scenery and stunts – including the famous cliff dives at La Quebrada in Acapulco. And the extensive use of music and singing, composed by Dimitri Tiomkin (future Oscar winner), was a first for any Tarzan film.

The nine months spent filming in Acapulco cemented Weissmuller’s special relationship to the place. He had first visited there in 1929, and had returned many times. Johnny and other members of the famed “Hollywood Gang” – including John Wayne, Red Skelton and Fred MacMurray – helped to put it on the map as a “jet set” vacation destination. They were even co-owners of the Los Flamingos Hotel there for many years. He would end up spending the last years of his life in Acapulco not far from that hotel, in a beautiful cliffside home overlooking the Pacific, and was laid to rest in a cemetery nearby…

Johnny had kept himself in good shape and was still very believable and universally beloved in the role of Tarzan. At age 43 he was powerfully built even though he might not have had the lean physique of his younger years. As biographer David Fury said, “This veteran Tarzan still fought his enemies with the heart of a lion and the strength of three men.”

Nonetheless, in 1948 Weissmuller decided that he would finally retire his loincloth. Part of the impetus was that Lesser would not give him a share of the revenue for the films, something which was just starting to become a more standard practice in Hollywood for the stars whose names were a big draw. Even right as he was retiring, Johnny’s Tarzan pictures were playing first run in foreign theaters and would do so for years to come, earning untold millions for MGM and RKO.

Shortly before Weissmuller’s retirement, A New York Times writer had this to say:

“Tarzan’s appeal to audiences is fundamental…you begin to see why nearly 140,000,000 people see every (Weissmuller) Tarzan picture, from New York to Bombay. In 1932 Johnny Weissmuller, an Olympic swimmer, was introduced as the Jungle king and ever since has dominated the field despite the appearance from time to time of minor incarnations. Weissmuller lives modestly in Beverly Hills…the only concession he has made to Hollywood is to marry three times; he still retains his simple and athletic tastes (and) spends a great deal of free time playing golf.”

After a legal separation of four years, Johnny’s divorce from third wife Beryl was finalized in January of 1948. They had tried their best to keep the family together for the sake of the children, but found no way to do so. Johnny stayed committed to fully supporting his kids in every way he could, and was always present in their lives when their mother allowed the visits.

A few years earlier, Johnny was playing his usual rounds at the California Country Club when he met Allene Gates, daughter of a pro golf celebrity and an accomplished amateur golfer in her own right. The friendship turned romantic after a couple of years, and they were wed shortly after the divorce. Johnny and Allene often traveled the country and the world to golf tournaments and exhibitions together, and their love of the sport provided a strong bond. The much younger Allene and Johnny would pass a number of happy years together, until the age difference and a serious financial downturn caused by his unscrupulous business manager took their toll.

As soon as Weissmuller retired from playing Tarzan, a producer at Columbia Studios offered him a percentage of the gross to do the lead in Jungle Jim, a film based on Alex Raymond’s comic strip. “If it sells, we’ll do a series”, he told Johnny. It was a big hit, and the series proved to be very financially lucrative for Weissmuller as well.

The “pulp-fiction” Jungle Jim adventure films were targeted to a young Saturday matinee audience and adults who were hard-core Weissmuller fans. Beginning in 1948 Johnny starred in sixteen Jungle Jim movies over eight years, all of which were financially successful and immensely popular – if not critically acclaimed. Both the films and the TV series were syndicated domestically and abroad for years thereafter.

Weissmuller continued to perform many dangerous stunts and all of the underwater fight scenes himself for both the movies and the 26 episodes of the Jungle Jim TV series that followed, well into his early fifties. Remarkably, the highest dive he ever did was for the opening of a Jungle Jim film – 76 feet off a cliff into a river.

In February of 1950, Weissmuller was by an overwhelming margin named the “Greatest Swimmer of the First Half-Century” by an Associated Press Poll of hundreds of the top sports writers and broadcasters from around the nation.

“There was no doubt that the tall, panther-like Weissmuller, a product of the public pools of Chicago, was to speed swimming what Jack Dempsey was to boxing, Babe Ruth to baseball and Bob Jones to golf. He shone in his field with brilliance and power…in sports’ dizzy, giddy and golden era of the tremendous Twenties.”

From the AP awards press release

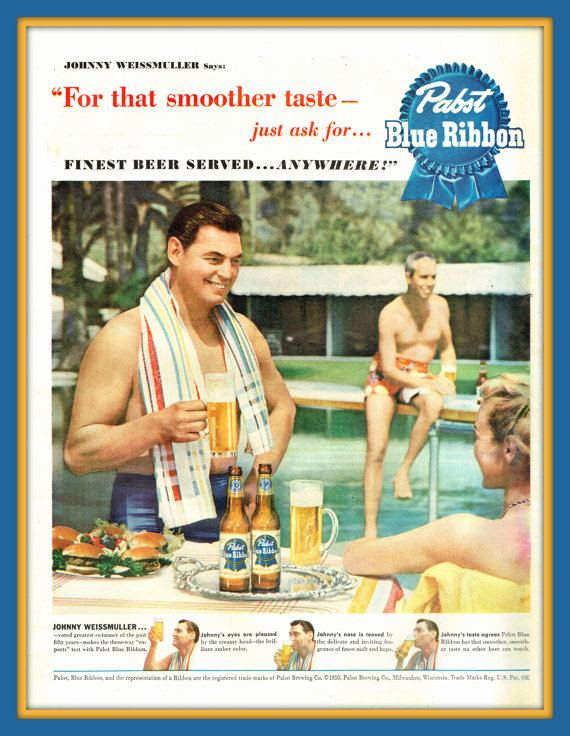

This prestigious sports honor renewed Johnny’s popularity as a champion athlete and further awards and accolades came pouring in. All these awards also meant Johnny was featured in a whole new series of ads and products. Of note is that this beer ad campaign was the only exception to Johnny’s policy of never promoting alcohol or cigarettes, as it was most important to him to exert a positive influence on the youth.

In 1954, MGM re-released his first two films to great success; a whole new generation now saw him in his prime on the big screen. In fact, most of the 12 Weissmuller Tarzan movies were re-released in theaters worldwide over the years.

And then the television era ushered in five more decades of widespread international viewing of those Weissmuller films, which are among the most broadcasted movies of all time.

By 1957, Weissmuller had retired from acting and went on to partner in various business ventures. In great shape in midlife, Johnny also continued to bring his popularity directly to his fans via water shows throughout the 1950’s.

He also traveled the world doing charity work throughout his life, always willing to lend his fame for a good cause when asked. He helped to open and fundraise for children’s hospitals in places like Istanbul and Madrid. One of his pet charities was the Special Olympics, and to that end in 1976 he donated all of his Olympic medals and many trophies to the Joseph P. Kennedy Foundation for disabled children, to be used in fundraising exhibitions. (They are now housed at the International Swimming Hall of Fame museum.)

In March of 1963, he married for the fifth and final time. He had met Maria Bauman Mandell a couple of years earlier at a charity luncheon in L.A. when Bing Crosby’s brother, Bob, introduced them. At that time they were both in marriages that were ending and so struck up a platonic friendship. Maria was born in Germany and had moved to the US in 1949 with her young daughter. Her first husband had been killed on the Russian front while she was pregnant, and she later became part of the underground resistance movement. Johnny and Maria were together for 21 years until his death, and he legally adopted her daughter Gunda Elisabeth (“Lisa”).

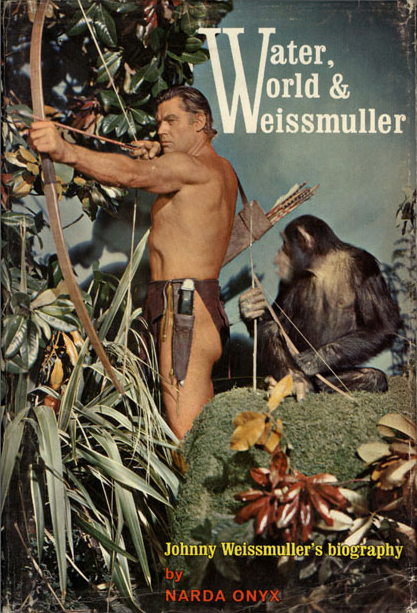

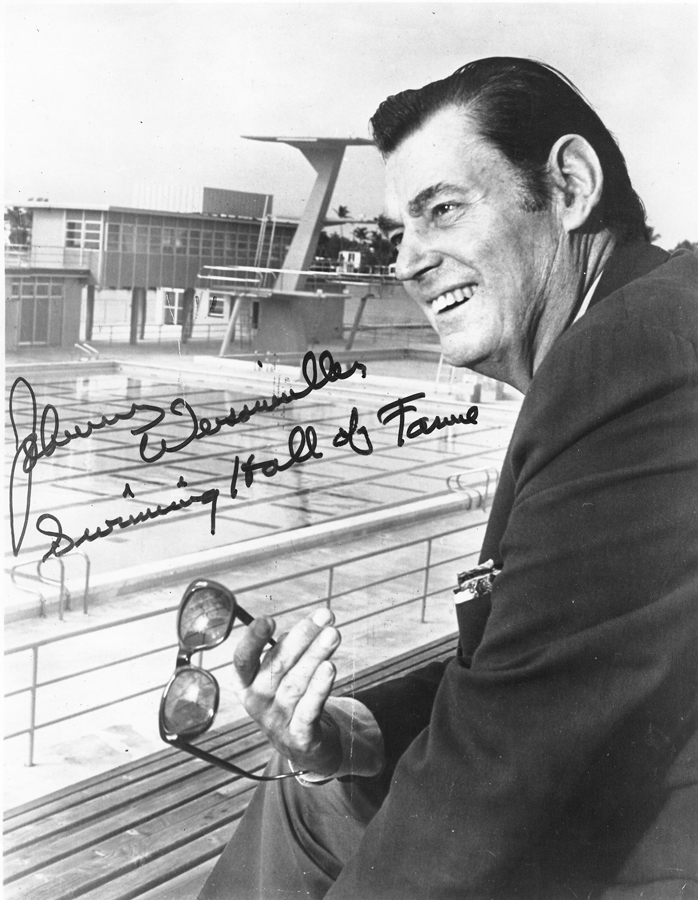

1964 saw the release of “Water, World and Weissmuller”, a biography by Narda Onyx that Johnny participated in so much it was pretty much an autobiography. It featured many stories from him and gave a lot of insight into his life’s journey. Unfortunately, he quickly had it pulled out of circulation when a misguided judge ordered all proceeds from the book sales be given to an erroneous claimant on his old movie royalty payments. It’s now a valued and rare collector’s item.

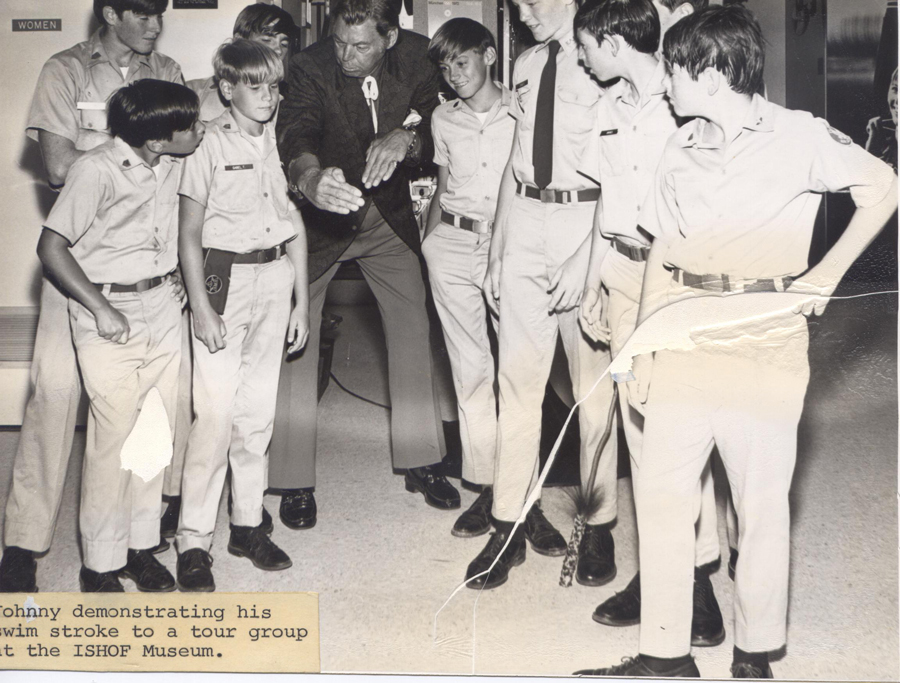

In 1965, Weissmuller was chosen to be the first honoree at the newly created Swimming Hall of Fame in Fort Lauderdale, FL. He was also a guest commentator for their first two nationally televised meets, on CBS’ Sports Spectacular. Johnny was given the title of Founding Chairman of the Board, and moved to Florida to be a more permanent part of it. He poured his heart into the endeavor, and the struggling organization would have floundered without his presence and reputation drawing donations from individuals and organizations. During the eight years he spent there he raised over a million dollars for construction and swimming programs.

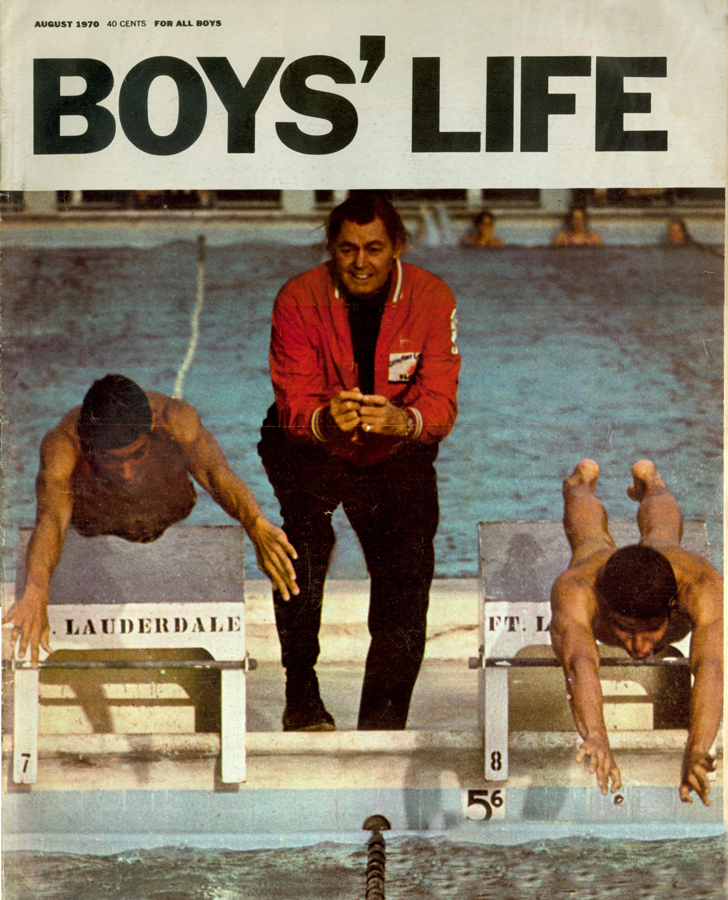

He would take almost daily swims in the Hall of Fame pool, and spent many afternoons there interacting with all of the young swimmers and divers. He appeared in magazines and on television and radio to promote the SHOF and swimming for all ages, but especially for children.

As Hall of Fame director Buck Dawson recalled in a 1984 tribute: “Johnny was still a spectacular swimmer in his late sixties… and he really helped us launch the Hall of Fame just by being around, even though we could not afford to pay him. He got other stars to appear (for us). Probably my biggest thrill in life was a trip to Jamaica with Johnny to promote the upcoming British Commonwealth Games…”

Something often overlooked about Weissmuller was his lifelong commitment to fitness and healthy food for all. In fact, in 1969 he helped establish a franchise – “Johnny Weissmuller’s American Natural Foods”. The stores were ahead of their time and played a key part in the health food movement.

“Maurice (White) turned us on to eating healthy as a group. We started going to health food stores together, places like Johnny Weissmuller’s American Natural Foods on Hollywood Blvd…” from Philip Bailey’s 2014 memoir, “Braving the Elements of Earth, Wind and Fire”

Every store opening he appeared at was mobbed, like the St. Louis one where over 1800 fans showed up. Due to the poor business practices of his partners the stores ended up being bought out or closed shortly thereafter, but they were precursors to today’s Vitamin Shoppe and Whole Foods stores.

Johnny said about them: “My food stores serve all kinds of vitamin pills, organic foods and protein bars. All good things which Mother Nature intended us to have but which modern living makes it hard to get. In years to come, the environment will be so tough on our systems that only the very healthy will survive well…”

In 1972, Weissmuller and four other great Olympians were honored to be part of a sterling silver commemorative set of medals depicting great moments in Olympics history. He was also featured that year in the Associated Press book The Sports Immortals, on the careers of the 50 athletes they deemed to be the greatest of all time.

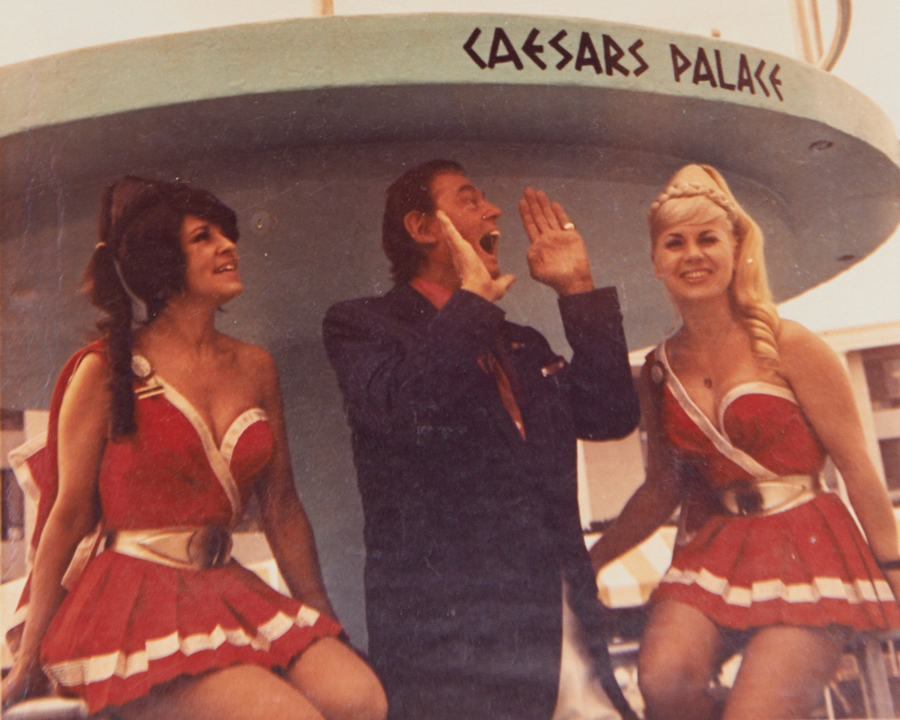

In the latter part of 1973 Johnny and Maria moved to Las Vegas in order to be closer to his children and grandchildren, who lived there and in California. As a man who loved to keep busy, Johnny never even considered full retirement – so to pass the time and pull in some extra money he worked in public relations at the Caesar’s Palace Hotel for a couple of years, along with his old friend Joe Louis. He played golf with high rollers and hung out with fans at the hotel. Many of his old celebrity pals performed or vacationed in Vegas, so he was able to reconnect with a lot of them at that time.

In August of 1977, he suffered a major stroke while in Los Angeles for a fundraiser. He needed fulltime care and thus lived for the next two years at the Country Home and Hospital, a convalescent home for veteran actors in California. When fans learned of his condition, he received nearly a hundred thousand letters and gifts from the world over.

After a legal dispute with the executive director of the place, Johnny and Maria moved to his beloved Acapulco for a while. He was still very well loved and known there, and was able to live in beauty and comfort with 24-hr attendants on their modest income. Both remained legal residents of California and hoped to move back there to live at some point, but for Johnny it was not to be.

In 1983, he was one of the twenty founding inductees to the US Olympic Hall of Fame. Though he was too ill to attend the ceremony he sent an acceptance statement with his daughter.

On January 20 1984, Johnny passed away at his seaside home in Acapulco after six years of courageously fighting for his health. He was survived by his wife Maria, children John, Wendy and Lisa, and six grandchildren.

World leaders and old friends, celebrities and common people, sent telegrams and cards of condolence. The extent to which his appeal crossed all political and ideological boundaries was proven by the fact that Weissmuller was one of the only figures to receive extensive obituaries on television in nearly every country worldwide, including the Soviet Union and communist China – something almost unheard of at the time.

Weissmuller was one of the very few non-heads of state ever to be afforded a 21-gun salute, at his memorial service at Good Shepherd church in Beverly Hills. Arranged by Senator Kennedy and President Reagan, it was a singular honor for a man who was a true American icon. Concurrent memorial masses were also held at St Michael’s in Chicago (where he had been an altar boy), St. Patrick’s Cathedral in NYC, and the Vatican in Rome.

Though he had endured many trials and tribulations in his life – growing up in a poor immigrant family with an abusive father, the untimely death of his teenage daughter Heidi and suicide of his beloved Lupe, financial ruin caused by his unscrupulous business manager of 25 years and his own debilitating series of strokes that rendered him so physically disabled the last few years of his life – Johnny was always happy-go- lucky, down to earth and considerate with everyone who crossed his path. And his legendary sense of humor, generosity and accessibility to his fans made him all the more beloved.

As good friend and former TV Tarzan Ron Ely said recently in a filmed interview:

“If you talk about Johnny Weissmuller, you can only say positive things. He was a positive person, and didn’t show his troubles on the outside. He had a lot of friends; everyone loved him. I didn’t know anyone to ever make the tiniest negative comment about Johnny…

And…he was just everybody’s favorite Tarzan, and he still is. People come up to my table when I’m signing pictures and they say, “well, Johnny Weissmuller was my favorite”. And I have to agree…he was mine, too; how can you argue that?”